The FairShare Model: Chapter Twelve

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-07-02

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Send comments to karl@fairsharemodel.com

Chapter 12: Calculating Valuation

Preview

- Foreword

- Pre-Money vs. Post-Money Valuation

- Calculating valuation - share method

- Calculating valuation - percentage method

- Valuation is not intuitive

- Price per share is not valuation

- Valuation -- Primary and Fully Diluted Shares

- Valuation Calculation Using the Fairshare Model

- Onward

Foreword

There a variety of ways that companies decide how and where to set their valuation. This chapter explains how to calculate it.

Pre-Money vs. Post-Money Valuation

"Valuation" is a slippery word because it can be understood to mean something different, depending on the context. The last chapter opened with some points to keep in mind when contemplating valuation issues. The most important one is that valuation is price, and that price is not necessarily worth. That's an idea that makes sense even if you don't know how to calculate the valuation.

If you are going to calculate or evaluate a valuation, it is similarly important to be mindful of the difference between a company's pre-money and post-money valuation. The difference is the money-the total investment. But there is also a difference in relevance-the pre-money valuation is the one that is important when money is being raised.

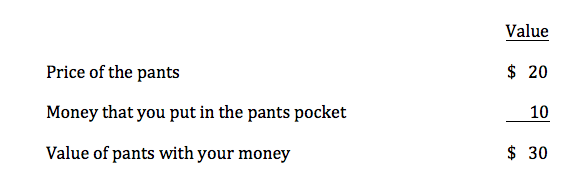

To help make the distinction between pre-money and post-money valuation clear, imagine a pair of pants offered for $20. You put $10 in the pants pocket. What is the value of the pants?

The first thing that you ask yourself is "When?" Before or after you put your money in the pocket? The $20 price is the analog of "pre-money valuation." The $10 that you put in the pocket is the "money" and the $30 is the "post-money valuation."

The pants are worth $30 after your $10 is in the pocket. That is, if the pants are worth $20 to begin with. If the pants are worth $15 before the money, they are worth $25 now. If the pants are worth $25 before the money, they are worth $35 now.

Clearly then, the answer to the question-- What is the value of the pair of pants?-depends on the context. Before or after the money? Just as clearly, the most important figure is the pre-money valuation-what the pants were worth before you put your money in the pocket. That is true for companies too.

With this metaphor in mind, let's return to the example in chapter ten, The Tao of the Fairshare Model. We have a company that raises $5 million from investors in exchange for half the company. The parties agree that the issuer's pre-money valuation is $5 million. The table below summarizes the deal. The post-money valuation of $10 million is equivalent to the value of the pants with your money. As with the pants, the figure to focus on the pre-money valuation-is the company worth that before the money is invested?

This chapter answers the question "How does one calculate the pre-money valuation?" Or, in the example, ""How can you tell that the pre-money valuation is $5 million?" It makes no judgment about whether it is too high, too low or just right.

Determining what the pre-money valuation is a simple, mechanical process. All you need a formula, a calculator and a few moments. Determining what pre-money valuation should be is a complex matter; the next chapter discusses that.

-----------------------------------

There are two methods to calculate it-using the number of shares outstanding or percentage of the ownership offered.

Calculating valuation - share method

Here's the formula to calculate the pre-money valuation using the outstanding shares method.

Pre-Money Valuation = Number of Shares Outstanding Before the Offering X Price of a New Share

If a company has 10 million shares outstanding before an offering and plans to sell new shares for $1.00, its pre-money valuation is $10 million. It doesn't matter how many shares it plans to sell, its pre-money valuation is $10 million. All that matters is how many shares are outstanding and the price of a new share.

Why a share is worth $1.00 is a more philosophic question. So is the question "Why are there 10 million shares already outstanding?"

Let's apply this formula to a fresh example. ABC Company has 10 million shares outstanding and plans to raise $5 million. To do so, it decides to issue 1 million new shares at $5.00 per share. With these terms, ABC gives itself a $50 million valuation (e.g., 10 million shares outstanding X $5.00).

After the offering, if someone sells a share of ABC stock for $6.00, or $1.00 higher than the offering price, the company's valuation-its market capitalization-will rise from $55 million to $66 million (11 million shares X $6.00).

Conversely, if the most recent share price is $4.00, ABC's valuation falls to $44 million (11 million shares X $4.00).

Whether ABC is privately held or publicly traded, the calculation assumes that stock is sold at market value, and, that the latest price is the value of each share outstanding. Theoretically, it is what someone would pay to buy the entire company.

Calculating valuation - percentage method

You can also calculate the pre-money valuation if you know the percentage of the company that an amount of money buys. The formula is:

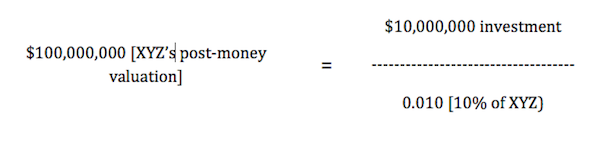

As you'll see in a moment, it is nothing more than a variation of the simple formula you've seen. Stepwise, first calculate the post-money valuation. That is what you get by dividing the investment amount by the percentage of the company.

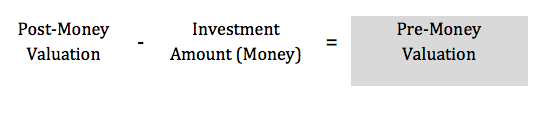

Next, subtract the investment amount to get the pre-money valuation.

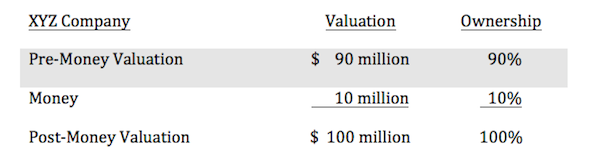

Let's apply this to an example. Say that 10% of XYZ Company is offered for $10 million. What is the pre-money valuation? First, calculate the post-money valuation, so, divide $10 million by 10%.

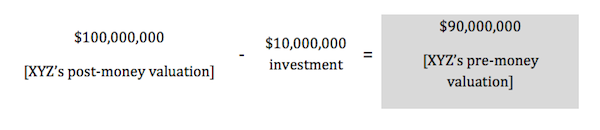

The result is a post-money valuation of $100 million. The second step is to subtract the amount of the new investment from the post-money valuation. That is the pre-money valuation.

For XYZ's, subtract the $10 million investment from the $100 million post-money valuation. The result is XYZ's pre-money valuation, which is $90 million.

You can tell this is correct because $10 million buys 10% of the company; $10 million is 10% of the $100 million post-money valuation.

Valuation is not intuitive

Unless you are a math whiz, you'll probably need a calculator to compute valuation, particularly using the percentage method. If you think you can eyeball it, be careful. To see why, let's examine how the pre-money valuation changes as the percentage of ownership by new investors changes.

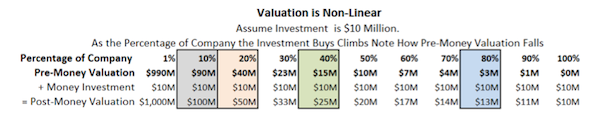

The table below shows how valuation has a non-linear relationship with a percentage of the compnay being bought. It shows the valuation range of XYZ Company, the one we just calculated the $90 million pre-money valuation for, given that $10 million buys 10 percent of the company. The table shows the pre-money valuation at mulitple points, ranging from 1 to 100 percent, assuming the amount raised is $10 million.

On the far left, it shows that if 1 percent of the company sold for $10 million, its pre-money valuation is $990 million and its post-money valuation is $1 billion (or $1,000 million). On the far right, it shows that if 100 perscent of the company sold for $10 million, its pre-money valuation is zero. Between those two columns are valuations for various percentages of ownership-the invesment amount is fixed.

Look at the column where 10 percent of the company is sold for $10 million-the pre-money valuation is $90 million and the post-money valuation is $100 million, just as calculated on the last page.

The next column has the valuation when the percentage purchased doubles, from 10 to 20 precent. Notice that the pre-money valuation changes disproportionately. It goes from $90 million to $40 million (i.e., it is not half of $90 million).

Now double the percentage pruchased again-go to the column where the percentage purchased is 40 percent and compare it to the 20 percent column. The change in pre-money valuation is again disproportionate, it goes from $40 million to $15 million.

Do it again. Double the percentage of the company purchased for $10 million from 40 percent to 80 percent. Note that the pre-money-valuation drops disproportionately, from $15 million to $3 million.

Could you calculate these pre-money valuations in your head? Would you, if you were evaluating a deal? Most people would want a calculator.

A takeaway point from the tables in Appendix A is that when half a company is for sale, the pre-money valuation is always the same amount as the amount raised. That is, if half the company is sold for $5 million, the pre-money valuation is $5 million. If half is sold for $20 million, the pre-money valaution is $20 million. If half is sold for $30 million, the pre-money valuation is $30 million and so on.

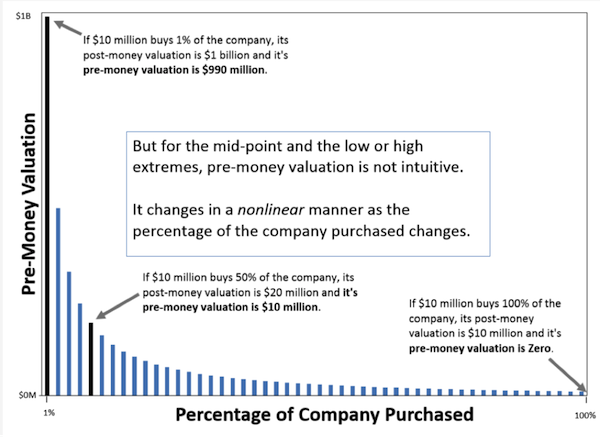

Another takeway is, for the most part, valuation is not intuitive-it needs to be calculated. Visually, this becomes clear from the chart below. It illustrates the non-linear relationship between the pre-money valuation and the percentage of the company sold for a given investment amount.

The chart above assumes the investment amount is $10 million. On the low end, if it buys 1 percent of the company, the post-money valaution is $1 billion and the pre-money valuation is $990 million. On the high end, If it buys the entire company, the post-money valuation is $10 million and the pre-money valuation is zero. If it buys half the company, the post-money valuation is $20 million and the pre-money valuation is $10 million, the same as the investment.

The curve is exactly the same regardless of the amount of the investment.

Price per share is not valuation

So, valuation reflects the number of shares outstanding and the share price. What that means is that an increase in the number of shares outstanding will increase the valuation unless the share price drops enough.

I suspect that many investors who buy publically traded stocks don't pay attention to market capitalization. Instead, they decide whether to buy or sell based on what the price per share is. Stock price behavior after a stock split suggests this is true. A two for one stock split, for example, gives shareholders two shares of stock for every one they have. If markets were rational, the post-split stock would trade at half pre-split price; after all, it's the same company with twice the number of shares. When companies do split their stock, however, its not unusual to see the stock price move up. Why? Investors who are valaution unaware bid the price up.

IPO pricing provides additional evidence that retail investors focus on the share price, not the valuation. Ever notice how IPO prices tend to fall within a range of $14 to $18 per share? It's subtle marketing. The psychology is similar to what happens in other forms of retailing. Items priced at $19.95 move better than those priced at $20.00 or $20.10. Cars sell better at $19,900 than at $20,000. This propensity of consumers to round down and of retailers to create psychological "hooks" has been studied for decades. [11]

Razzle-dazzle elements infuse most forms of marketing. When an item has utility like a car, travel, food, or a pair of pants, buyers are better able to distinguish value from price, but razzle dazzle is nonetheless effective at persuading them to pay more.

When the item marketed is an investment-something without utility-buyers are far more likely to focus of things that may not be as important, like price per share.

Valuation -- Primary and Fully Diluted Shares

Valuation calculations focus on shares that have been issued and are outstanding. A complication is introduced when a company has committed to issue shares in the future under certain circumstances. For example, the company have given investors who have lent the company money the right to convert the debt owned to stock at a pre-set price (i.e., convertible promissory notes). More commonly, stock options and warrants have been issued that result in new shares being issued at a pre-set price if and when the right to do so is exercised.

These are examples of "contingently issuable" shares or share equivalents-stock that is not outstanding but can reasonably be construed to be. When accountants report a company's earnings per share, they have two measures, "primary" and "fully-diluted". [12] Primary EPS is the earnings for the period divided by the average number of shares outstanding during that period. Fully diluted EPS is the same calculation except that the denominator also includes unissued shares that meet criteria for being "contingently issuable."

There is no uniform answer for how to deal with contingently issuable shares when calculating valuation. When VCs assess a company's pre-money valuation, some, but not all, include a new employee stock option pool in the shares outstanding even when the option plan doesn't exist yet, and it will take years for shares to be issued. When this occurs, the new investors (the "money") effectively says to the existing shareholders "all dilution that will result from the option plan to motivate employees must come out of your share of ownership." By contrast, market makers and professional investors for traded stocks focus on the relationship between the issued shares and shares that are available to trade, the "float." They tend to ignore unissued shares and issued shares that will not affect the trading market in the near term.

The issue of contingently issuable securities is beyond the scope of this book, which is to provoke support for the Fairshare Model. However, this will be a topic of discussion for entrepreneurs and those involved in financial reporting and services…once they see that there is significant investor interest in the model.

Valuation Calculation Using the Fairshare Model

In the Fairshare Model, a very large block of Performance Stock is outstanding at the IPO. For example, if one million shares of Investor Stock is outstanding after the IPO, there could be ten or twenty million shares of Performance Stock. The reason there is a high ratio of Performance Stock is that it is intended to motivate performance for years-possibly a decade-and it may be harder for legal, tax or accounting reasons to issue new Performance Stock after a company is public.

The sheer number of shares of Performance stock is not important. Regarding voting rights, Performance Stock is capped at 50 percent of the vote (or whatever is proscribed in an issuer's incorporation documents). Regarding dilution of Investor Stock, what matters is the conversion rules. On this last point, think of a dam. From the perspective of the town downstream from the dam-the Investor Stock in this analogy-it doesn't matter how much water is behind the dam, which represents the Performance Stock. What matters is the release rate of the water.

How much of the Performance Stock will convert? That depends on the company's performance and the rules established by the Investor and Performance Stock shareholders. Broadly speaking, it seems likely that some will convert, but there is no reason to assume that all of it will. And of course, the further out one looks, the harder it is to project what the performance will be and what the market value of the company will be, both as a result of the performance and any conversions that occur.

When calculating pre-money valuation, I believe that Performance Stock should be excluded from the basic valuation calculation based on primary or issued shares because they can never trade and any liquidation preference that it has is of de minimis or trivial value. Should they be considered in a fully-diluted style valuation calculation? Probably, but it makes sense to estimate the enterprise value that might result from the anticipated performance.

This is a complex topic. I've thought about it lightly and there are several angles to this subject. Expert opinions may vary and I look forward to dialogue on it.

How should such shares affect the valuation calculation? If a company has a stock option plan for employees, has issued warrants to purchase stock or has debt that could convert into shares, they can affect how valuation is calculated.

The question is arcane to the target audience for this book, most of whom are valuation unaware. And, I don't think they care.

What they care about, I believe, is how to make it possible for…Middle Class investors to make venture capital investments on terms comparable to those that professional investors get.

That's the prize that all eyes should be set on.

Onward

If you know a company's valuation, how do you evaluate it? How do you identify what is reasonable? What's a deal? What's out of line?

[11] In his 1957 book, The Hidden Persuaders, Vance Packard, compared the use of motivational research and other psychological techniques to ''the chilling world of George Orwell and his Big Brother.'' http://www.nytimes.com/1996/12/13/arts/vance-packard-82-challenger-of-consumerism-dies.html

[12] "As converted" is a scenario for defining outstanding shares when there is debt that could convert to shares, but hasn't. Typically, investors assess private companies on this basis as well; it falls between actual shares outstanding and full-diluted shares. It's unlikely to be relevant in the Fairshare Model; pre-IPO investors will most certainly prefer to convert their debt to tradable Investor Stock.

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.