The FairShare Model: Chapter Nine

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-04-06

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Chapter 9: Cooperation as the New Tool for Competition?

Preview

- Foreword

- Big Solutions to Big Problems are Hard to Find

- Cooperation as a model for competition

- The size of the prize (or the economic pie)

- The power of cooperation as a model for competition

- Cooperation in animals

- What Does Adam Smith Say About Human Nature?

- Common Purpose is what you make it

- Isn't "Maximization of Shareholder Value" the Common Purpose?

- Diversity in Common Purpose

- A Common Purpose Panorama

- Onward

Foreword

John Donne was an English poet, satirist, lawyer and priest who died in 1631. He wrote this piece [112], which has always touched me:

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were: any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.

Those who benefit from the return on capital have a stake in addressing the social anxiety about the diminished return on labor. Few would challenge that, yet there is little agreement on what to do about it.

Higher taxes on income, capital gains, and inherited wealth are favored by the left. Reducing regulation and promoting business interests in the hope of growing the pie are favored by the right. Tax code simplification and improved worker training has supporters on both sides. Shifting the tax focus from income to consumption will be subject to debate. For some, the allure of trade agreements is dubious, but that die is pretty much cast—nations see net positive results for enhancing the integration of economies.

No matter what emerges from the policy making process, it is apparent that the supply of labor will continue to grow, as will the use of robotics. The result will be continued pressure on the return on labor, relative to the return on capital.

By now, you recognize that the Fairshare Model relies on cooperation between the Investor and Performance Stock. Some will view this as a weakness. In this chapter, I'll argue that the ability of capital and labor to cooperate could be a competitive strength that helps companies outperform rivals, be they business competitors or rivals for desirable employees.

As you go through it I'd like you to contemplate how this ability, when combined with efficient and transparent capital markets, offers five important macro-economic benefits to a society:

1. Better matching capital with opportunity should generate economic growth and job creation (see chapter seven);

2. Encouragement of an economy's indigenous ability to innovate (see chapter seven);

3. Expand the ranks of those who participate in the return on capital (see chapter eight);

4. Broader pursuit of an Aristotelian Good Life, the concept that Edmund Phelps discusses in Mass Flourishing, will be encouraged (see chapter seven); and

5. Promote Wall Street IPOs that are less gamed (see chapter three) and more in line with John Rawls' Theory of Economic Justice (see chapter eight).

As you prepare to flip the page, I hope you appreciate that the Fairshare Model is a Big Idea, but it is not a Big Solution to the macro-economic problems of capitalism. Rather, it is a market-driven micro-economic idea that is focused on the interests of a very small group—public investors in a venture-stage company's IPO. Of secondary importance are the interests of entrepreneurs and their pre-IPO investors. Collectively, we're not talking about a lot of people. A few thousand per year while the model is in the early adopter phase. A few hundred thousand annually once it enters the mainstream market, but significantly more as the model grows in acceptance. That's how ideas lead to change in societies—gradually.

The Fairshare Model is not a utopian idea—it is intended to be a practical idea to foment innovation and growth in the economy, and directly help capitalism work better for a few more people and, indirectly, for a larger number.

Big Solutions to Big Problems are Hard to Find

Philosophers have long puzzled, "What system most benefits a society?" The question lurks as gripes about how capitalism is practiced increase. The discussions focus on how things end-up, whether it's wealth concentration, wage levels, environmental issues or other concerns. These are Big Problems.

For some, the solution for a Big Problem is a Big Solution; something revolutionary. The U.S. Marshall Plan for Europe and the social security system were Big Solutions to Big Problems. The problem with a Big Solution is that they can appear Too Big to gain broad support. And, all indications are that it will be difficult to find broad support for Big Solutions to the problems of weak economic growth and rising income inequality.

Of course, objections to Big Solutions tend to melt in the face of a common threat because it promotes common cause. In America, the creation of securities laws followed the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The Patriot Act ushered in transformative changes in banking and travel after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act strengthened financial reporting controls after a series of scandals at large firms. Concern about how the benefits of capitalism are distributed is mounting in the streets and in the suites of executives and policy makers, but it hasn't jelled to "a common threat for which there is a shared response." As a result, the potential for solutions inspired by common threat is unclear.

Common values foster common cause, but not always effective action. Some societies that share values—Germany, Sweden and Canada come to mind—seem less likely to need a Big Solution because they address problems before they become a Big Problem. Other societies can be crippled by shared values. The desire to avoid disharmony helps explain the difficulty that Spain, Greece and Japan have responding effectively with their economic problems.

For a variety of reasons, it's increasingly difficult to find common cause. It's ironic, because each of us can reach more people, more rapidly, with more information than ever before. Miguel de Cervantes' fictional character Don Quixote undertook a quest to change the world and right all wrongs while practicing respect and promoting civility toward others. Quixote would surely despair at the current state of social dialog, captured by one humorous observer who suggests that the most frequent sentence used over the Internet is "You're an Idiot!" with the second being "It's a Hoax!" [113]

Sociologist Robert Putnam examines this phenomenon in his 2001 book, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. He notes that civil society is breaking down as Americans become more disconnected from their families, neighbors, communities, and the republic itself. Organizations that gave life to democracy are fraying. He adopts bowling as a metaphor, observing thousands of people once belonged to bowling leagues but nowadays, they're more likely to bowl alone. He writes that: [114]

Television, two-career families, suburban sprawl, generational changes in values--these and other changes in American society have meant that fewer and fewer of us find that the League of Women Voters, or the United Way, or the Shriners, or the monthly bridge club, or even a Sunday picnic with friends fits the way we have come to live. Our growing social-capital deficit threatens educational performance, safe neighborhoods, equitable tax collection, democratic responsiveness, everyday honesty, and even our health and happiness.

So, there is little prospect of a Big Solution to the problems of economic growth and income inequality. That's because there is insufficient support for something revolutionary, no commonly perceived threat and it is difficult to find common cause based on philosophy, values or beliefs in what capitalism should deliver, even though it is generally viewed to be the best system.

The "best system" question is ancient, by the way. Around 380 B.C., in a dialogue known as The Republic, the Greek philosopher Plato presented a utopian idea, one where citizens who completed fifty years of rigorous training would be "philosopher-kings" with the wisdom to fairly distribute resources so there was no poverty. The Republic "has few laws, no lawyers and rarely sends its citizens to war, but hires mercenaries from among its war-prone neighbors (these mercenaries were deliberately sent into dangerous situations in the hope that the more warlike populations of all surrounding countries will be weeded out, leaving peaceful peoples)." [115]

Wikipedia notes that the word "utopia" was coined about two thousand years later by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, which described a fictional island society in the Atlantic Ocean. Then it adds:

The word comes from the Greek: οó ("not") and τóποç ("place") and means "no-place". The English homophone eutopia, derived from the Greek εὖ ("good" or "well") and τóποç ("place"), means "good place".

Homophones are words that sound the same but are spelled differently and have different meanings (e.g., assistance and assistants; sear and seer; fair and fare). Knowing that, you'll be amused by Wikipedia deliciously pointing out that:

"Because of the identical English pronunciation of "utopia" and "eutopia", it gives rise to a double meaning" —for it sounds like both "no place" and a "good place.

Utopia may be a mythic place, but the desire to find it can have great consequence. The most spectacular example in the 20th Century was the epic struggle over whether the world economies would be controlled by an idealized state or by imperfect markets. It was a battle over whether communism or capitalism would most benefit mankind. It began intellectually, with competing ideas about what was the "best system" for society, then manifested into physical and economic combat.

This struggle was the subject of the 1998 book, The Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy by Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw, which was made into a three part PBS series by the same name in 2002. I cannot recommend this more highly to anyone with interest in the role that economics played in recent world history. Here is how the the first episode opens: [116]

PROGRAM NARRATOR: This is the story of how the new global economy was born, a century-long battle as to which would control the commanding heights of the world's economies -- governments or markets; the story of intellectual combat over which economic system would truly benefit mankind; the story of epic political struggles to implant those ideas on the nations of the world.

EFFREY SACHS, Professor, Harvard University: Part of what happened is a capitalist revolution at the end of the 20th century. The market economy, the capitalist system, became the only model for the vast majority of the world.

NARRATOR: This economic revolution has defined the wealth and fate of nations and will determine the future of the planet.

DANIEL YERGIN, Author, Commanding Heights: This new world economy is being driven by technological change and by political change, but none of it would have happened without a revolution in ideas.

Ultimately, communism failed everywhere, no country could make it work remotely close to its ideal, let alone as an admirable, sustainable system. This is evidence that capitalism is a better system but it does not mean that it can't be improved. Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism, a book mentioned in chapter seven, points out that there is variation in how it is practiced; the dynamics in the U.S. differ from what they are in Canada, Germany, Great Britain, Sweden, Japan, Australia and South Korea, for instance.

What will define the epic struggle of the 21st century? Imagine what answers might have been offered about the 20th century a hundred years ago, as WWI was unfolding. It is unlikely that many would have guessed correctly as there was no competing ideology to capitalism.

I imagine that the 21st century will be defined by competition for resources and spheres of influence, stoked by conflict regarding values, beliefs and attitudes—traditional versus modern. The toll that modern society wreaks on the planet may well be the epic struggle, and it may involve nuclear devastation, be it by accident, war or terrorism. But these are not conflicts about economic systems. If the question is focused on that, I imagine that the defining challenge of the 21st century will be "How can the benefits of capitalism best be shared?"

Cooperation as a model for competition

I posit that the ability to cooperate will emerge as an important form of competition in the 21st century. I mean cooperation within and between micro-networks, not the sort of broad-based societal cooperation that relies on an overly optimistic view of human nature.

Micro-networks exist within an enterprise, its supply chain and its customer base. Within an enterprise, they exist between classes of shareholders, shareholders, directors and top management, top management and other employees and amongst non-employees. These micro-networks are layered on, and interacting with, each other—like themes in a musical fugue. They are partnerships with shifting and overlapping interests that center on whether the company is doing well. Micro-networks in successful companies favor positive, self-renewing ways of interacting while companies that generate negative, discordant themes are prone to dysfunction and eventual failure.

How might the benefits of capitalism best be shared? To be broadly supported, an answer must appeal to people with diverse philosophical views and also be practical. Since micro-networks are narrow, self-selecting associations of people, it is easier to define an approach that meets their needs than society at large. In other words, rather than a Big Solution, I propose a mosaic of Small Solutions to the Big Problem facing contemporary capitalism writ large.

Micro-solutions suit our times. There is no global economic threat that motivates joint action. [117] Common ties are weaker and world-views increasingly fractured; there is more talk about succession than about coming together. Students of history know that long before most countries were nation-states, they functioned as city-states, provinces, states or tribal regions. Perhaps we're reverting to what's natural; humans favor a smaller definition of common interest over the one Donne advanced during the Enlightenment.

Although many bemoan that assessment, few will disagree with it. There are good-hearted souls who wish to change that. While they work on it, I'll just accept that it's simply the course that we're on. And, suggest that the ability to cooperate could be be a competitive tool for those who invest in or work for companies that adopt the Fairshare Model.

The size of the prize (or the economic pie)

If cooperation is the means of competition, what is the competition for? What is the size of the prize or the economic pie? It has two components.

1. Economic growth that results from increasing productivity, and

2. Expanding the ability of working class people to participate in the increase in valuation that occurs in venture-stage companies.

The first component is straightforward. As discussed earlier, new companies are the engine of economic growth and job creation. In his 2013 book, Rebooting Work, Maynard Webb observes that:

The speed at which companies come and go, succeed and fail, is different from even a short while ago. The half-life of a company is diminishing incredibly quickly. One-third of the companies listed in the 1970 Fortune 500 were gone by 1983. (They were acquired, merged, or split apart.) The average life expectancy of a company in the S&P 500 has dropped from seventy-five years (in 1937) to fifteen years today. [118]

Despite the shortened life-expectancy of companies, the U.S. economy has grown, fueled by new companies that offer ways to be more productive. Efforts to improve their ability to raise equity capital, therefore, can make a positive contribution to economic growth.

The size of the second component is large and hard to quantify, but is apparent when you think about it. It's the wealth earned by betting on the valuation of companies and it has two elements:

A. The increase in valuation that takes place when it is privately held, between its inception and when it is acquired or goes public,

B. The increase in valuation that occurs in the secondary trading market.

The collective amount of wealth that has been generated in recent decades by these two segments has been enormous and it has gone to a relatively small portion of society. The Fairshare Model has the potential to change this because it facilitates better investment opportunities for unaccredited investors. If public investors did fractionally as well in their investments as venture capitalists, it would be a better return than they can get otherwise (and involve more fun). [119]

Also, when Performance Stock converts to Investor Stock, a portion of the wealth created by an increase in the company's valuation goes to employees. At present, that portion goes to investors in the secondary market. Some of them trade based on better access to information than most investors. When a company uses the Fairshare Model, some of this wealth goes to the people whose work leads to the increase in valuation. That is, more wealth will go to those who create it and less will go to those who trade on information.

The power of cooperation as a model for competition

The ability of cooperation to be an effective competitive weapon was powerfully demonstrated by Toyota Motor Co. The so-called "lean manufacturing" concept that it pioneered is associated with concepts like zero defects and just-in-time inventory management. In such a system, micro-networks must collaborate, cooperate and communicate extensively. In contrast, variations of the "scientific management" philosophy favored by Toyota's larger competitors fostered an adversarial, command-and-control management style that emphasized time-study efficiency but fostered workplace alienation.

In his 2008 book, The Toyota Way to Healthcare Excellence: Increase Efficiency and Improve Quality with Lean, John Black writes: [120]

Sakichi Toyoda, who founded the Toyota Group, was the inventor of a loom that would stop automatically if any of the threads snapped. His invention reduced defects and raised yields, since a loom would not continue producing imperfect fabric and using up thread after a problem occurred. The new loom also enabled a single operator to handle dozens of looms, revolutionizing the textile industry.

The principle of designing equipment to stop automatically and call attention to problems immediately is crucial to the Toyota Production System (the foundation of Lean Manufacturing). This is the system of "jidoka", the intelligent use of both people and technology, with the ability (even the obligation) to stop any process at the first sign of an abnormality.

When the Toyota Group set up an automobile manufacturing operation in the 1930's (replacing the Toyoda family's "d" with a "t"), Sakichi's son, Kiichiro headed the new venture. He traveled to the U.S. to study Henry Ford's system in operation. He returned with a strong grasp of Ford's conveyor system and an even stronger desire to adapt that system to the small volumes of the Japanese market.

Soon thereafter, the first Toyota system of manufacturing was born. To say that Toyota copied Ford is not accurate---Toyota learned from Ford, especially from Ford's mistakes. This demonstrated the power of the Toyota system: continuous improvement. It was in some ways a revolution, just as Ford's had been but the differences were often striking.

I want to pause to point out that the scientific management approach to cost and quality has dramatically lost favor with manufacturers since the 1980s. Now, most of them—certainly many who are competitive with regard to cost and quality—have adopted variants of lean manufacturing or just "lean" when its principles are applied to non-manufacturing activities. As Black's book title indicates, that includes healthcare, which may surprise many; it affects design of operating rooms, nurse stations, management of supplies, accounting practices, etc.

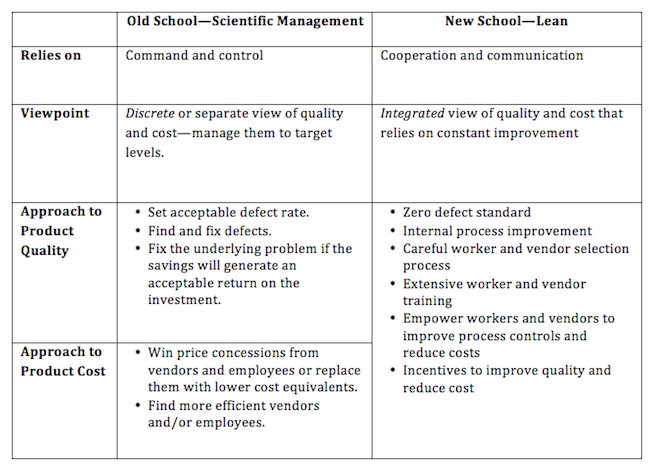

The table below highlights how differently these two schools of management thought-the "old school" scientific management approach and the "new school" lean approach-address the Big Problems of how to build quality products and control costs.

In the scientific management mindset, the Big Problem is the defect, not the process that created it. The solution was to inspect for quality and repair defects. A process improvement requires a cost/benefit justification. [121] Workers were replaceable cogs who were expected to keep the production line going, not to change a process. If they didn't keep up, they were fired. Vendors were pressured to reduce their price without collaboration as to how to do it.

In a lean system mindset, the Big Problem is a process that creates defects; a defect is a symptom of a Big Problem. Workers are empowered to stop a process if they see a defect. What follows is an intense search for the cause and a way to prevent it in the future. Suppliers are trusted partners who are transparent about their process—they collaborate with the manufacturer on ways to improve processes so costs come down and quality improves.

These two approaches differ in the importance of cooperation. They can also be contrasted by the type of relationships they promote, between employer and employee, and between a company and its suppliers. Scientific management tends to ignore the humanity of relationships while the lean approach acknowledges it.

My admiration for what Toyota accomplished is enhanced by my background. I grew up in the Detroit area, exposed to labor strife. My first job after college was at Ford Motor, performing cost/benefit analysis on transmissions while the scientific management approach was the standard and the Toyota Way was obscure. A few years later, in 1984, my then-spouse helped bring up the accounting department at New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI) the Fremont, California joint venture between Toyota and General Motors that explored the portability of the Toyota system to the U.S. [122]

After a stint in purchasing, where she worked with NUMMI suppliers, she then left to work for the United Auto Workers union. So, I had the opportunity to observe this unique enterprise from different perspectives, like a piece of art. One takeaway was appreciation for how many constituencies a business has—shareholders, lenders, employees, customers, suppliers and the community—and how well NUMMI balanced them. Another was those who advocate on behalf of a single interest have a less complex job than businesses.

Another, very different, experience informs my perspective on the power of cooperation. In the mid-'80s, I worked for a Silicon Valley telecom manufacturer called Granger Associates. Just before I was hired, it had been acquired by a company with a centralized command and control style. It used an annual and five year planning process that was similar to what many companies had. Granger Associates' processes was different. It had been defined by a serial turnaround executive named Quentin Thomas Wiles (everyone referred to him as "Q.T.") who was also chairman of a San Francisco investment firm, Hambrecht & Quist. He was known as "Dr. Fix-It" as a result of a long and impressive record of revitalizing companies in a turnaround situation. In an article called "The Green Berets of Corporate Management", he was quoted as saying "I think I can fix anything." [123]

Q.T. left Granger when the transaction took place, so I never met him, but virtually every executive I worked with initially had worked for him. It was through them and from study that I came to understand his philosophy and methods for performance definition, measurement and reward. I learned that he applied a variation of the same structure in other turnarounds, and, that there were people who worked with him at more than one company.

Goal setting in Q.T.'s system was done quarterly. There was intense focus was on the next quarter, with slight attention to the remaining quarters in the year. There was no multi-year plan. Q.T. felt that a company makes it's year one quarter at a time, therefore, focus on the one in front of you. A key result of the planning process was to define the "5 Most Important Tasks" for each bonus-eligible manager. In Q.T.'s system, one's salary was about 80% of what the market rate was. If they earned their full quarterly bonus, their compensation could be 120% or more than market. So, the company had 20 opportunities a year (5 quarterly tasks times 4 quarters) to align interests in a tangible way with each manager. Each set of tasks reflected what a manager could affect—sales, production, inventory levels, product development targets, etc. The system, unsurprisingly, had a powerful effect on behavior. As quarter-end approached, those who had not yet accomplished their goals were highly focused on achieving them, if feasible. Higher level management monitored who was on track and who wasn't. They then took steps to try and make up the shortfall in one division with overachievement in another.

The theme of this chapter is cooperation. It existed at Granger—the esprit de corps was high. But the spirit of cooperation did not flow from, as I described earlier, cooperation that relies on an overly optimistic view of human nature. Rather, it flowed from well thought out understanding of a problem, goals to achieve, clear communication, accountability and the ability to influence outcomes. It was the spirit of cooperation that flowed from trust and confidence in oneself and in others. This was the result of Q.T.'s organizational philosophy. [124]

As a whole, Granger Associates made its quarterly targets. There was a vitality and dynamism in that organization that was the best I've ever seen. Compared to the annual plan approach favored by Granger's parent, indeed, by most U.S. companies, Q.T.'s approach unleashed the equivalent of what John Maynard Keynes might have have described as an organization's "animal spirits," a sense of purpose in the face of uncertainty. A significant reason was that managers had input on what their goals were and had the resources they needed to meet them.

After Granger Associates, one of Q.T.'s turnarounds, became his Waterloo. Miniscribe Corporation, based in Longmont, Colorado became infamous for fraudulent financial reporting. To meet targets, some managers at this publicly traded disk drive manufacturer falsified their performance, which came to light in an audit. Someone who knew Q.T., his system and people at Miniscribe told me that the system worked well when people shared an ethos that kept them from doing something wrong. He said that it failed at Miniscribe because some people did not understand where to draw the line.

These anecdotes illustrate facets of three important points about cooperation in the workplace. The first is that companies with cooperative micro-networks improve their odds of success. It only took Toyota a few decades to become the largest automaker in the world. The strength of its micro-networks was an important factor to its eventual triumph, for these networks helped make lean practices work. There is reason to believe that other companies, even start-ups, can achieve greater success with strong micro-networks of their own. In Silicon Valley, for example, the importance of a collaborative workforce and supply chain are well recognized.

The second point is that a reward system can evoke and direct cooperation. That's particularly true when the goals are specific and relevant, when the incentive goes deep into the organization and the reward for achievement is issued frequently enough to maintain the incentive.

The third point is that a good system can deliver a bad result. Q.T. Wiles' system had an impressive record: Miniscribe did not invalidate it. Other approaches to motivate employees have bad results too. Similarly, if a company applies the Fairshare Model ineffectively, this should not invalidate it. It's not a utopian solution but it's a promising one, if you subscribe to the idea that cooperative micro-networks have the potential to be a game-changer in the tough business of growing a business.

Few readers will question the advantages that accrue from a series of cooperative micro-networks. But some will feel this relies on an idealized notion of human society, and point out that its our nature to compete, to be selfish, to be sneaky or aggressive in order to advance one's interest. To the extent that that is true, that undercuts the notion that micro-networks of investors and employees can cooperate in a way that enables the Fairshare Model to function effectively.

Time and experience will test how well the Fairshare Model works. But, the next section will challenge the premise of this view of human nature. The idea that cooperation and fairness, indeed, empathy and compassion, qualities that John Donne expresses in the poem at the start of this chapter, are not natural human qualities.

Cooperation in animals

Some readers may accept the benefits of cooperation but be skeptical about the potential to achieve it.

"Humanity is actually much more cooperative and empathic than its given credit for" says Frans B. M. de Waal, a biologist known for his work on primate behavior. In 2007, Time named him one of The Worlds' 100 Most Influential People Today. In 2011, Discover had him among 47 (all time) Great Minds of Science. In November 2011, de Waal gave a TED talk—Moral Behavior in Animals [125]—on the capacity of primates to reconcile, share and cooperate. My edit of it for brevity and readability, is below.

I [Frans de Waal] discovered that chimpanzees are very power hungry and wrote a book about it. And at that time, the focus of animal research was on aggression and competition. I painted a whole picture of the animal kingdom, humanity included, that said deep down we are competitors, we are aggressive, and we're all out for our own profit basically.

But in the process of researching power, dominance and aggression, I discovered that chimpanzees reconcile after fights. And so what you see here [pointing to the screen] are two males who have had a fight. They ended up in a tree, and one of them holds out a hand to the other. And about a second after I took the picture, they came together in the fork of the tree and they kissed and embraced each other.

Now this is very interesting because at the time everything was about competition and aggression, and this didn't make sense. The only thing that matters is that you win or that you lose. But why would you reconcile after a fight? That doesn't make any sense.

The principle we found is that when you have a valuable relationship that is damaged by conflict, you need to do something about it. So my whole picture of the animal kingdom, including humans, started to change.

So we have this image in political science, economics, the humanities, and philosophy that man is like a wolf—deep down, our nature is nasty. I think it's a very unfair image for the wolf. The wolf is, after all, a very cooperative animal; that's why many have a dog, which has these characteristics also.

And it's unfair to humanity, because it is more cooperative and empathic than its given credit for. So I started getting interested in those issues and studying that in other animals.

If you ask, "What is morality based on?" two factors always come out.

- One is reciprocity, and associated with it is a sense of justice and a sense of fairness.

- And the other one is empathy and compassion.

Human morality is more than this, but if you would remove these two pillars, there would be not much remaining--they're absolutely essential.

(Video of two experiments are shown that demonstrate the point.)

We also published an experiment where the question is, "Do chimpanzees care about the welfare of somebody else?" It's been assumed that only humans worry about the welfare of others. We found that the chimpanzees care about the well-being of others -- especially, members of their group.

The final experiment that I want to mention is about fairness. It has been performed in many ways. I'm going to show you the first experiment that we did with capuchin monkeys but has been done with dogs, birds and chimpanzees.

We put two monkeys in a test chamber side-by-side, so they see each other. These animals know each other. Each has a simple task to do to get a reward-hand us back a rock. The reward is a piece of cucumber. As you can see, they're perfectly willing to do this repeatedly. Cucumber is fine for them, but they prefer grapes. If you give one monkey cucumber and the other a grape, you create inequity between them. That's the fairness experiment.

In the videotape, the one on the left gets cucumber for returning the rock to the researcher.

(Monkey on the left gets rock from researcher, returns it and gets a cucumber reward)

The first cucumber is perfectly fine as a reward for the one on the left. The first piece she eats.

(Next, the monkey on the right hands gets from researcher, returns it and gets a grape reward.)

Then she sees the other one on the right get a grape for the same task. Watch what happens.

(Monkey on the left that got cucumber shows envy of the monkey on the right that got the grape)

The one on the left again gets the rock, gives it back, and gets a piece of cucumber.

(Audience howls when the monkey on the left throws back the cucumber at the researcher.)

(More laughter as the monkey extends her arm to reach for the out-of-reach grape dish. Frustrated and angry, she shakes her cage and slams her hand on the table to get the attention of the researcher.)

(Continued laughter when the sequence is repeated and the monkey on the left remains angry)

So this is basically the Wall Street protest that you see here. (Uproarious audience laughter)

Let me tell you a funny story about this. This study became famous and we got a lot of comments, especially from anthropologists, economists, philosophers. They didn't like this at all. Because they had decided that fairness is a very complex issue and that animals cannot have it.

One philosopher wrote that he would believe it had something to do with fairness if the one who got grapes refused them. Now the funny thing is, an experimenter who used chimpanzees had instances where, indeed, the one offered the grape refused it until the other also got one.

So we're getting very close to the human sense of fairness. And I think philosophers need to rethink their philosophy. I think morality is much more than what I've been talking about, but it would be impossible without these ingredients that we find in other primates, which are empathy and consolation, pro-social tendencies and reciprocity and a sense of fairness.

Thus, professor de Waal provides reason to believe that humans, the most highly developed primate, naturally have the social qualities that are necessary for the Fairshare Model to work.

What Does Adam Smith Say About Human Nature?

In 1776, the year America declared its independence, Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith published An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations. This book, known as The Wealth of Nations, is the cornerstone of classic economic thought, where market forces are a likened to an "invisible hand." Less known is his 1759 book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments which explores the moral underpinnings for commerce, the "system" that came to be known as "capitalism."

Economist Russ Roberts is a fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution. In 2014, he authored a book, How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life: An Unexpected Guide to Human Nature and Happiness. In it, he writes that The Theory of Moral Sentiments "was Adam Smith's attempt to explain where morality comes from and why people can act with decency and virtue even when it conflicts with their own self-interest. It's a mix of psychology, philosophy, and what we now call behavioral economics, peppered with Smith's observations on friendship, the pursuit of wealth, the pursuit of happiness, and virtue. Along the way, Smith tells his readers what the good life is and how to achieve it."

Defenders of convention in the capital formation process—today's high valuations and the way Wall Street IPOs are allocated—may be taken aback when Roberts reports that "Smith wrote on the futility of pursuing money with the hope of finding happiness." [126] To those who believe capitalism is about self-interest and that "greed is good", Roberts lets it be known that there is nothing about that in The Wealth of Nations and the opposite is true in Theory of Moral Sentiments, which minimizes the importance is constantly seeking fame, power and money. He offers this quote from the first page of Theory of Moral Sentiments leads me to think that Adam Smith and John Donne shared views about human nature.

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. [127]

Roberts says that Smith felt that, deep down, what humans really want is to love, to be loved and to be admired. And, that these motivations are the foundation of civilization. By the way, Roberts is rather hip for an economics professor. He hosts Econtalk (www.econtalk.org), a podcast on economic matters. He also helped create a YouTube video in which dueling views on the nature of economic cycles are delivered in rap-style. From a personal perspective, he writes "Smith helped me understand why Whitney Houston and Marilyn Monroe were so unhappy and why their deaths made so many people so sad. He helped me understand my affection for my iPad and my iPhone, why talking to strangers about your troubles can calm the soul, and why people can think monstrous thoughts but rarely act upon them. He helped me understand why people adore politicians and how morality is built into the fabric of the world."[128]

Roberts also writes "Economics helps you understand that money isn't the only thing that matters in life. Economics teaches you that making a choice means giving up something. And economics can help you appreciate complexity and how seemingly unrelated actions and people can become entangled." [129]

Common Purpose is what you make it

You might believe that cooperative micro-networks are an advantage for a company, and, that a model that encourages cooperation would appeal to investors and workers. You might also believe that it is natural for people to want to cooperate and still wonder what the objectives of the cooperation might be. What would be the common purpose?

In the Fairshare Model common purpose, the measures that convert Performance Stock to Investor Stock, can be whatever the participants agree that it will be! And, it can change as often as they want it to change.

The measure of common purpose will vary by company, and it can change over time. Classic measures would be revenue, margin and profit. But, those may be insignificant for a young company and not applicable to a start-up that seeks capital to develop its product. It could be development of intellectual property, a product release, measures of customer satisfaction, securing new financing on favorable terms. It could even include a community based measure of value like the number of jobs or environmental impact.

Isn't "Maximization of Shareholder Value" the Common Purpose?

"Are you a socialist?" Someone asked me that after seeing concept material that I had online about the Fairshare Model. The idea that employees could vote on shareholder matters and share in the return on capital prompted his question. I'm not a socialist; I'm a capitalist who is seeking a better deal for public investors in venture-stage companies. And, I think that a capital system that emphasizes fairness, embraces empathy and promotes cooperation—that is, the Fairshare Model—has the potential to help its adopters outperform those that rely on one that doesn't (i.e., a conventional capital structure).

That said, the question begs other, larger ones. Such as "Who does a corporation owe a duty to?" and "Are some stakeholders more important than others?" A company's constituencies are varied; shareholders, the CEO, other employees, customers, suppliers and the communities it operates in. How do they rank in priority?

Under U.S. bankruptcy law, when a company enters a "zone of insolvency", its board of directors and management must place the interests of creditors before shareholders or anyone else. An enterprise can be in this zone when its current assets (cash, accounts receivable, inventory) exceeds its current liabilities. In other words, when it lives hand-to-mouth from a cash perspective; they lack the ability to pay their obligations in full and in the ordinary course of business.

This becomes interesting when one considers that many venture-stage companies reside much of the time in the zone of insolvency. Their hope of moving to a better neighborhood rests on confidence that investors or lenders will provide the capital that allows them to be solvent-this includes the willingness of creditors to wait for payment. Therefore, if such a corporation were a person, it might be cast as Blanche DuBois, the character in Tennessee William's A Streetcar Named Desire who utters the line "I have always depended on the kindness of strangers." [130]

Put that thought to the side though. There is a deeper question to contemplate, "How do the stakeholder's rank in priority when a company is not financially distressed?" Jack Ma, the CEO of Alibaba famously said that his ranking is "Customers first, employees second and shareholders last." He didn't have a place for creditors. That may be because in 2014, his Chinese company (actually, a Cayman Island affiliate) had the largest IPO in the history of the U.S. (or the world).

Like me, Dear Reader, you may be aware of management teams who operate as if their interests trump everyone else's; they're more important than those of customers, other employees, creditors or shareholders. This world view is rarely articulated. When it is, it is usually as a justification for exposed behavior. I don't recall a CEO advancing "It's all about me!" as a legal or business theory on priority but I've seen evidence that some believe it.

Common wisdom is that a corporation's highest duty is to maximize the interests of its shareholders.

Washington Post business columnist Steven Pearlstein challenges that orthodoxy in a brilliant 2013 piece entitled How the Cult of Shareholder Value Wrecked American Business. I recommend that you read the entire article but excerpts are below [bold added for emphasis]. [131]

In the history of management ideas, few have had a more profound — or pernicious — effect than the one that says corporations should be run in a manner that "maximizes shareholder value." Indeed, you could argue that much of what Americans perceive to be wrong with the economy these days — the slow growth and rising inequality; the recurring scandals; the wild swings from boom to bust; the inadequate investment in R&D, worker training and public goods — has its roots in this ideology.

The funny thing is that this imperative to "maximize" a company's share price has no foundation in history or in law. Nor is there any evidence that it makes the economy or the society better off. What began in the 1970s and '80s as a corrective to managerial mediocrity has become a corrupting, self-interested dogma peddled by finance professors [132], money managers and over-compensated corporate executives.

[Apparently, no law requires] that executives and directors owe a special fiduciary duty to shareholders. How then did "maximizing shareholder value" evolve into such a widely accepted norm of corporate behavior? The most likely explanations are globalization and deregulation, which together rob many major American corporations of the outsize profits they earned during the "golden" decades after World War II. Those profits were enough to satisfy nearly all the corporate stakeholders. But in the 1970s, when increased competition started to squeeze profits, it was easier for executives to disappoint shareholders than their workers or communities.

No surprise, then, that by the mid-1980s, companies with lagging stock prices found themselves targets for hostile takeovers by rivals or corporate raiders using newfangled "junk" bonds to finance their purchases. Disgruntled shareholders were willing to sell. And so it developed that the threat of a possible takeover imbued corporate executives and directors with a new focus on profits and share prices, tossing aside inhibitions against laying off workers, cutting wages, closing plants, spinning off divisions and outsourcing production. Today's "activist investor" hedge funds are the descendants of these 1980s corporate raiders.

While it was this new "market for corporate control" that created the imperative to boost near-term profits and share prices, an elaborate institutional infrastructure has grown up to reinforce it. This infrastructure includes business schools that indoctrinate students with the shareholder-first ideology and equip them with tools to manipulate earnings and share prices. It includes lawyers who advise against any action that might lower the share price and invite shareholder lawsuits, however frivolous. It includes a Wall Street that is fixated on quarterly earnings, quarterly investment returns and short-term trading. And most of all, it is reinforced by pay packages for executives that are tied to the short-term performance of the company stock.

The result is a self-reinforcing cycle in which corporate time horizons have become shorter and shorter. The average holding periods for stocks, which for decades was six years, is now less than six months. The average tenure of a public company CEO is less than four years. And the willingness of executives to sacrifice short-term profits to make long-term investments is rapidly disappearing.

The real irony surrounding this focus on maximizing shareholder value is that it hasn't, in fact, done much for shareholders. One thing we know is that less and less of the wealth generated by the corporate sector was going to frontline workers. Another is that more of it was going to top executives. Almost all of that increase came from stock-based compensation.

One problem is that it's not clear which shareholders it is whose interests the corporation is supposed to optimize. Should it be the hedge funds that are buying and selling millions of shares every couple of seconds? Or mutual funds holding the stock for a couple of years? Or the retired teacher in Dubuque, Iowa, who has held it for decades?

Even as [corporations] proclaim their dedication to shareholders, they have been doing everything possible to minimize and discourage shareholder involvement in corporate governance. This hypocrisy is recently revealed in the effort by the business lobby to prevent shareholders from voting on executive pay or to nominate a competing slate of directors.

For too many corporations, "maximizing shareholder value" has provided justification for bamboozling customers, squeezing suppliers and employees, avoiding taxes and leaving communities in the lurch. For any one profit-maximizing company, such behavior may be perfectly rational. But when competition forces all companies to behave in this fashion, it's hardly clear that society is better off. Perhaps the most ridiculous aspect of "shareholder uber alles" is how at odds it is with every modern theory about managing people. David Langstaff, CEO of TASC, a government contracting firm, put it this way:

"If you are the sole proprietor of a business, do you think that you can motivate your employees for maximum performance by encouraging them simply to make more money for you? Of course not. But that is effectively what an enterprise is saying when it states that its purpose is to maximize profit for its investors."

These days, economies have been scrambling to explain the recent slowdown in the pace of innovation and the growth in worker productivity. Is it possible it might have something to do with the fact that workers now know that any benefit from their ingenuity or increased efficiency is destined to go to shareholders and top executives?

The defense you usually hear of "maximizing shareholder value" from CEOs is that most of them don't confuse this week's stock price with shareholder value. They acknowledge that no enterprise can maximize long-term value for its shareholders without attracting great employees, producing great products and services and doing their part to support effective government and healthy communities. In short, they argue, there is no inherent conflict between the interests of shareholders and those of other stakeholders.

But if optimizing shareholder value requires taking care of customers, employees and communities, then you could argue that "maximizing customer satisfaction" would require taking good care of shareholders, employees and communities. And, indeed, that is the suggestion made by Peter Drucker, the late, great management guru. "The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer," [he] wrote.

It is no coincidence that companies that maintain a strong customer focus - think Apple, Johnson & Johnson and Procter & Gamble - have done better for their shareholders than companies which claim to put shareholders first. The reason is that customer focus minimizes risk taking and maximizes reinvestment, creating a larger pie from which everyone benefits.

Most executives would be thrilled if they could focus on customers rather than shareholders. In private, they chafe under the quarterly earnings regime forced on them by asset managers and the financial press. They fear and loathe "activist" investors who threaten them with takeovers. And they are disheartened by their low public esteem.

If it were the law that was at fault, that would be easy to change. Changing a behavioral norm — one reinforced by so much supporting infrastructure — turns out to be much harder. The challenge facing the "corporate social responsibility" movement is that it exhibits an unmistakable liberal bias that makes it easy for academics, investment managers and corporate executives to dismiss it as ideological and naïve.

My guess is that it will be a new generation of employees that finally frees the American corporation from the shareholder-value straightjacket. Young people — particularly those with skills that are in high demand — today are drawn to work that not only pays well but also has meaning and social value. As the economy improves and the baby boom generation retires, companies that have reputations as ruthless maximizers of short-term profits will find themselves on the losing end of the global competition for talent. In an era of plentiful capital, it will be skills, knowledge, creativity and experience that will be in short supply, with those who have it setting the norms of corporate behavior.

How might people respond to debate about what common purpose for a corporation should be? For some, it will be disorienting to consider that maximizing shareholder value isn't the sole answer. For others, it will be liberating.

The ability, indeed, the responsibility, to define common purpose seems a bit daunting. In some ways, it is more stressful to have a choice than to have it already defined. In this sense, those who use "maximize shareholder value" have had it easy.

What's clear is that more than one answer is possible, and, that the rationale for the conventional one is not as strong as many may think.

Diversity in Common Purpose

Steven Pearlstein deconstructs a precept that is central to defenders-of-the-way-things-are. The notion that the only purpose of a corporation is to advance the interests of its shareholders. Increasingly, there are people who want new thinking about corporate purpose, which is an expression of common purpose. In a way, this is like people who like athletics finding value in something other than winning.

A "benefit corporation" or "B corp" for short, is an example of this. It is a new class of incorporation, one whose charter includes a duty to benefit society. Since 2010, nearly thirty U.S. states have authorized them. The accounting and tax rules are the same as for a regular corporation, also known as a "C corp." What is different is that directors in a B corp have a duty to consider the interests of all "stakeholders"-shareholders, employees, suppliers, customers, community and environment-when deciding matters. An article in The New Yorker expands on this: [133]

Whereas a regular business can abandon altruistic policies when times get tough, a benefit corporation can't. Shareholders can sue its directors for not carrying out the company's social mission, just as they can sue directors of traditional companies for violating their fiduciary duty. Becoming a B corp raises the reputational cost of abandoning your social goals. It's what behavioral economists call a "commitment device"—a way of insuring that you'll live up to your promises. Being a B corp also insulates a company against pressure from investors.

Since the nineteen-seventies, the dominant ideology in corporate America has been that a company's fundamental purpose is to boost investor returns: as Milton Friedman put it, increased profits are the "only social responsibility of business." Law professors still debate whether or not this is legally true, but most CEOs feel huge pressure to maximize shareholder value. At a B corp, though, shareholders are just one constituency. [The clothing company] Patagonia doesn't need to worry about investors' opposing its environmental work, because that work is simply part of the job. For similar reasons, benefit corporations are far less vulnerable to hostile takeovers. When Ben & Jerry's was acquired by Unilever, in 2000, its founders didn't want to sell, but they believed that fiduciary duty required them to. A benefit corporation would have had an easier time staying independent.

In his full Washington Post article, Pearlstein argues for tax and regulatory reforms that "help the corporate ecosystem become more heterogeneous." Biodiversity is good for the planet and social diversity creates a more vibrant, interesting society. It makes similar sense to promote diversity in the purpose of capitalist enterprises. Pearlstein says we ought to encourage "different companies taking different approaches and adopting different priorities." Because, "In the end, 'the market'—not just the stock market, but product markets and labor markets as well—would sort out which worked best."

To wit, the Fairshare Model presents a different approach to how venture capital is raised from the public and to how employees are compensated for their contributions. And, the model supports heterogeneity in how to define common purpose. Different companies will defined it differently—the model does not require a corporation to be "good." It does, however, call for conscious agreement on what it is; how performance is defined and measured.

A Common Purpose Panorama

Now, let's open the view on how the Fairshare Model addresses the common purpose challenge. To begin with, most companies that adopt the model will use shareholder value to measure performance. It is the best understood and accepted performance measure. Indeed, it can be a "gimme", enabling a company to say to its IPO investors, "If the market value of Investor Stock climbs from the IPO price, that's performance, or, evidence that you got a below market deal—either way, the Performance Stockholders get a reward." More on this in the next chapter.

Also, companies will have additional measures of common purpose—performance that generates conversions. They can be legal, technical, marketing or financial accomplishments—even measures of accomplishment that are social or environmental oriented. Plus, they can change it as they see fit. So here, common purpose is not a top-down Big Solution, nor does it require buy-in from a broad number of people. Instead, it's a bottoms-up micro-solution, formed by those who choose to deal with the issue. As a result, there is no large social or policy matter to argue about—it is live and let live.

However defined, the Fairshare Model requires common purpose between the issuer and the shareholders of Investor Stock and Performance Stock. So, the model strikes a bargain based on how the parties define performance—which is their common purpose. Issuers will vary in how they define it, but guidelines will emerge. They will vary based on the issuer's industry—software vs. food vs. industrial vs. service vs. biotech vs. service businesses—and stage of development. And, they may be applied differently based on the geography and other factors. For this reason, the model will be associated with diversity in what the purpose of a corporation is.

The model requires common purpose between the Investor and Performance Stockholders. What about within the Performance Stock pool? Investor Stock shareholders may have little interest in this—time and experience will tell. At this stage, one can only imagine the potential of Performance Stock to build common purpose. Once there is broad interest in the model, experts in law, tax, organizational behavior and other areas will assess this matter. For now, contemplate these ideas:

- Employees — Strategies to motivate employees often rely on team-building and creative thinking exercises. Their effectiveness fades as the novelty passes. Financial incentives have an enduring effect, so it is surprising that they are often overlooked. A Performance Stock program has the potential to foster common purpose and performance much like Q.T. Wiles innovative system did.

- Suppliers — "Lean systems" have ways to build common purpose in a supply chain but its relatively rare (in the U.S., anyway) for a company to offer suppliers equity in itself as incentive. An interest in Performance Stock, possibly a non-voting version, could provide a start-up a way to add more win-win aspects to the relationship.

- Investors — Performance Stock could be a "sweetener" for pre-IPO investors, providing incentive to support a low IPO valuation and the conversion rules. Also, it could be used to attract investors who can help the issuer but don't manage an investment fund. For instance, an angel investor group might be persuaded to advise the issuer in exchange for a chunk of Performance Stock. Their involvement could comfort other investors; they would be positioned to advise an unproven entrepreneurial team without having the legal exposure associated with being on the board of directors.

Performance Stock will present accounting and tax issues that will need to be evaluated by experts if there is a market for the Fairshare Model. In a later chapter, I'll have some things to say about the accounting implications. But here, I just want to encourage creative thinking about how it can be used to foster cooperation among links in an enterprise's value chain, its micro-networks.

Investor Stock can be used to promote common purpose too. Because it is sold in a public offering, anyone can buy shares. As a result, entrepreneurs that promote social good in their business have more investors to appeal to for support. Businesses that don't have this focus can nonetheless make their Investor Stock available to customers and suppliers.

The focus of these points about common purpose is the issuer and its micro-networks, not society-at-large. But, small solutions can help address big problems like weak economic growth and rising income inequality. With that thought in mind, reflect on what U.S. Secretary of Labor Thomas Perez had to say before the National Press Club on October 20, 2014:

I'm confident that we can construct a fair way to share prosperity in which everybody has a chance to live their highest and best dreams. And that's what I want to talk to you about.

This stairway has a number of important steps. Starting with tearing up the talking points and understanding history. Shared prosperity is not a fringe concept, cooked up by socialists. Historically, both parties have embraced it in both their words and, indeed, their actions. It's a principle that is as American as apple pie and is the linchpin of a thriving Middle Class.

Here's what Teddy Roosevelt said. "Our aim is to promote prosperity and then to see that that prosperity is passed around and there is a proper division of that prosperity." Lloyd Blankfein, CEO of Goldman Sachs, talked about the destabilized effects of income inequality and said "Too much of the GDP over that last generation has gone to too few of the people." Standard and Poors recently issued a report saying that income inequality is stifling GDP growth at a time when we're still climbing out of the Great Recession. Federal Reserve chairman Janet Yellin said "The extent of the continuing increase of inequality greatly concerns me." [134]

Onward

This chapter was about cooperation and common purpose. There is evidence that people (and animals) thrive when it exists. There is also reason to believe that companies that have a high degree of it in their micro-networks outperform those who have less of it.

The next chapter will examine the quintessential difference between a conventional capital structure and the Fairshare Model-how they deal with uncertainty. It will also discuss the causes of uncertainty.

[112] Meditation XVII, by John Donne

[113] "I've Discovered the Internet's Most Internet Sentence, and Your [sic] an Idiot if You Disagree" by Matthew Malady, New Republic, http://www.newrepublic.com/article/116769/your-idiot-internets-most-internet-sentence

[114] Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, by Robert Putnam, page 367

[115] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utopia

[116] It may be viewed on the PBS website http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/hi/story/index.html

[117] Climate change is a broadly perceived threat but not one that yet motivates joint action.

[118] Rebooting Work; Transform How You Work in the Age of Entrepreneurship, by Maynard Webb and Carlye Adler, Jossey-Bass, page 52

[119] Take another look at the charts in chapter two, the section called "A Bird's-Eye View of Possible Outcomes."

[120] The Toyota Way to Healthcare Excellence: Increase Efficiency and Improve Quality with Lean, John Black with David Miller, page 28-29, Health Administration Press

[121] My first job out of college was to analyze the cost/benefit of such solutions for a Big Three automaker.

[122] The NUMMI JV was liquidated in 2010 and its former facility is now the home of Tesla Motors.

[123] "The Green Berets of Corporate Management"

[124] Q.T. describes his organizational philosophy in this February 1988 interview with INC: "Company Doctor Q.T. Wiles," http://www.inc.com/magazine/19880201/7561.html

[125] View Professor de Waal's TED talk here http://www.ted.com/talks/frans_de_waal_do_animals_have_morals

[126] "How Adam Smith Can Change Your Life " by Russ Roberts, page 3

[127] Ibid, page 3

[128] Ibid, page 5

[129] Ibid, page 13

[130] In his 2012 presidential campaign, Mitt Romney declared that "corporations are people too"-a position consistent with the U.S. Supreme Court's 2010 decision in the Citizen's United case which found that corporations have a constitutional right to exercise free political speech (i.e., give unlimited money to political causes).

[131], "How the cult of shareholder value wrecked American business" by Steven Pearlstein, Washington Post, Sept. 9, 2013, http://wapo.st/18Kr1yY

[132] The seminal role that university finance professors played in promoting the policies that led to the Great Recession was highlighted in Charles Ferguson's Academy Award winning 2010 movie, Inside Job. It reports how eminent academics have made fortunes from Wall Street since the 1980s while advocating its interests in regulatory proceedings, the courts and in the media. A number promoted positions as objective experts while failing to disclose that they earned considerable sums from those who benefit from their policy prescription. Ferguson draws an ethical comparison to a physician who promotes the benefit of a drug as a medical expert but fails to disclose that he/she has been paid large sums by the company making the drug.

[133] "Companies With Benefits", by James Surowiecki, The New Yorker, Aug. 4, 20014 http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/08/04/companies-benefits

[134] http://www.c-span.org/video/?322184-1/labor-secretary-thomas-perez-us-economy

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact: Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.