The Fairshare Model: Chapter Six

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-04-10

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Chapter 6: Fairshare Model History & Projection

Preview

- Foreword

- My Path to the Fairshare Model

- How the Fairshare Model will emerge

- The Concept Gap

- Onward

Foreword

This chapter describes how I came to the Fairshare Model and how I expect it will emerge to become the New Normal for companies that seek to raise venture capital in a public offering.

My Path to the Fairshare Model

My path to the Fairshare Model became clear in the early 1990's, when I began offering consulting chief financial officer or controller services to start-ups in the San Francisco Bay area.

Preceding that, I worked for two Fortune 500 manufacturers in the Midwest, then at some smaller ones in Silicon Valley. Two of these California companies were remarkable for very different reasons. One had a strong performance-driven culture that had been established by a turnaround manager who had a long run of success. The other was a start-up that failed in spite having every possible predictor of success that one could imagine.

As a consultant, I saw companies that seemed deserving of investment that could not get the attention of venture capitalists. As I learned about the capital formation process, I discovered it to be rife with inefficiencies and bias.

One client was an environmental technology start-up. It had licensed technology from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratories to use an electron beam to transform certain toxics into harmless components. Environmental technologies were uninteresting to VCs then, so, the company turned to angel investors. This method of fund raising worked but took a long time and led to inefficient development efforts. We wound up turning to a consultant with connections to a broker-dealer to raise private capital via convertible debt, not equity; this turned out to be expensive money in several respects.

As I discussed the challenges with John G. Wilson, another consultant from San Antonio, Texas, he described a long-standing vision that he had for an alternative approach to raising equity capital. It involved small public offerings, small investors and a performance based capital structure. The capital structure was the Fairshare Model.

It was fanciful in many respects, but beguiling. We worked on it for a few months; identifying issues with what we now call equity crowdfunding and ways to resolve them. Mostly, we worked figuring out how to explain the concept and define a business model. We shelved the effort when we realized that the cost to print and mail offering documents was too high to make it work for issuers, given the low likelihood that a given mailing would result in an investment. Not only that, some states required that an offering document be cleared by its regulators before it could be mailed to a potential investor in that state. Their regulatory model was to regulate the offer of securities. The cost for this review was another barrier to feasibility; one had to pay the fee before one knew if anyone in that state would invest…or what amount.

October 1995, the heavens parted. The SEC announced that it was adapting its regulations to the then-emerging Internet Age. Electronic delivery of documents would be equivalent to the mail (i.e., one could email documents). Also, it would regulate the sale of securities, not the offer. The fact that the federal securities regulator took this position meant it would change the laws of the states.

The economics became feasible…potentially. There was so much still to evaluate.

We formed a company named Fairshare, Inc. and worked to implement John's core idea. Before 2001, when Fairshare sank in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, we had some success.

We were a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding (a/k/a "too early"). We showed that there was significant investor interest in the potential to invest in small companies using the Fairshare Model. We had 16,000 "opt-in"members, some of whom were enthusiastic enough to buy a paid membership ($50 or $100), but most signed up for our free membership. Unique visitors to our website was a multiple of our membership – it offered education on IPO deal structures and valuation. We had calculators to calculate valuation in multiple ways. That was the satisfying part—we discovered there was a market for the Fairshare Model.

The unsatisfying part was that we underestimated the difficulty we would face with securities regulators. It took far more time and money to find a place where securities regulators appeared satisfied with what we planned to do.

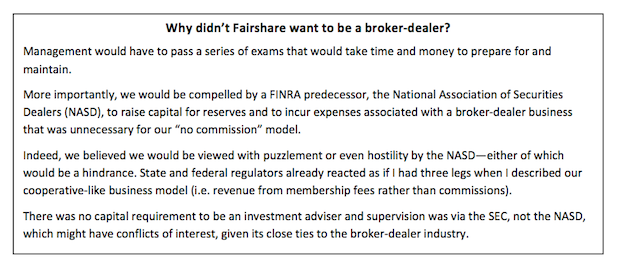

The core problem was that we positioned Fairshare to operate as a non-regulated entity.

We planned to build an Internet based community that, once it reached critical mass, could attract companies who wanted to pitch a direct public offering. Members would be able to pool due diligence. We said we would allow an issuer to pitch their DPO to our members for free (no commission) so long as it adopted the Fairshare Model and agreed to let members invest as little as $100. Fairshare would not handle investor cash or the issuer's stock but would influence the allocation of shares to members. Our plan was to make money from membership fees and, possibly, advertising; we had no intention of making money on investment transactions.

We saw ourselves as creating a web community. It would be a bit like Facebook, which launched about seven years later, in 2004. In ours, investors would be able to connect, learn about investing in start-ups and pool due diligence. It would also be an investor oriented version of Consumer's Reports, where our obligation was to our members.

Within months of launching the membership program, the securities regulatory agency for California had issued a "cease and desist order", stopping us from offering memberships to California residents. It said a membership—even a free one—was an investment contract….a security. As such, Fairshare would have to file a registration statement and presumably hire a broker-dealer to offer them. An administrative law judge denied our appeal. On its website, the California Department of Corporations identifies its decision is a "precedent case", one of six. You can see the list of cases here http://www.dbo.ca.gov/ENF/decisions/default.asp and read the ruling of the administrative law court here http://www.dbo.ca.gov/ENF/decisions/288.pdf , which is identified by the agency as the following.

Respondents: FairShare, Inc., aka FairShare Capital Markets; Karl M. Sjogren and John G. Wilson

- Dept. file number: ALPHA

- OAH file number: N-1998110288

- Law(s) involved: Corporations Code §§ 25019, 25110, 25532

- Date of Decision: January 26, 1999

- Summary: Desist & Refrain order issued under Corporations Code § 25532 upheld based on finding that "membership interests"in "internet-based"organization were "investment contract"securities under both "traditional"and "risk capital"analyses.

A few quarters later, we had queries from regulators in Ohio, Colorado and Texas. A membership was not a security under their law. [63] However, these states wanted to see a regulated entity involved when an offering was discussed and allocations of shares were managed.

To quell this concern, we formed a subsidiary that registered as a regulated Investment Advisor with the SEC and all states, including California. Eventually, we planned to ask the Department of Corporations if this would lead it to remove its cease and desist order on the offer of Fairshare memberships in California, but we had more pressing concerns. We needed more capital, to revise our approach to the business and more people.

I was tired. I had kept consulting CFO/Controller work as my "day job"during this 3 year effort. Doing that preserved our capital for expenses and for others who needed to be paid in order to work on Fairshare activity. John and I were also becoming frustrated with each other's view on how Fairshare should develop; a philosophic difference emerged.

John saw Fairshare as a closed system where the only offerings presented to members were DPOs that used the model and passed our screening. He did not want to see broker-dealers presenting offerings because he felt they would always be based on a conventional capital structure and, therefore, present an inferior deal to members. He also wanted to see the administration of Performance Stock for all issuers controlled by a single trust (i.e., a legal organization administered by a board of trustees). His view was akin to a strong central government or, to use a technology reference, a "walled-garden."A walled garden describes the experience used by America Online (AOL) back then and, nowadays, by Apple for its iPhones. John channeled the sentiment expressed in Apple's iconic "1984"super bowl ad, but to him, the enemy of the people was Wall Street, not IBM.

My view was evolving into a strong local government model, or, to use a technology reference, the approach favored by Microsoft's Windows operating system or Google's Android platform. I felt that members would prefer offerings based on the Fairshare Model, but that they would be most interested in the dynamics of a community. That is, the ability to share insight, be a target audience for any offering that met the standards of the community. So, I was open to the idea of offerings that used a conventional capital structure and/or were sold by a broker-dealer being brought to our members. I felt that if we could "organize the buyers"and help them learn how to be savvier, market forces would move issuers to provide lower valuations and stronger investor protections. So, I saw a walled—garden as inhibiting what investors ultimately wanted—wide choice and the safeguards for quality and safety. Also, I saw a central trust to administer performance stock programs as an unnecessary complication; issuers should be free to choose who administered them.

We debated our perspectives as we explored options to raise more capital. Then, the SEC notified our subsidiary that it intended to rescind its registration as an investment advisor. The reason? We did not qualify to be one because we did not manage member's accounts nor were they paying us for advice!

Joseph Heller's novel, Catch 22, came to mind. [64]

Our business model was to not be a financial intermediary —we had no plan to handle anyone's money or stock-—instead, we wanted to be a trusted social intermediary.

Clearly, we sought to operate in novel territory. Because it wasn't shared by other regulators, I viewed California to be an outlier whose position could be addressed with time (and expense). By forming our investment adviser subsidiary, we seemingly addressed the underlying concern—that we would facilitate investments without being a regulated entity. But now, the solution that promised to satisfy (most) states was at risk of being rescinded by the SEC's because we were not doing what states were concerned we might be do in the future.

Our round peg did not fit in the federal agency's square hole and state regulators wanted us to find a regulated place for our peg.

We were in a regulatory No-Man's Land.

We entered discussions with an investment group about buying the company. The principal investor was a member of a nationally-known family with powerful political connections. Plus, he had experience in the securities business. He was prepared to re-cast Fairshare as a broker-dealer.

Two days before we were to close, we learned that the SEC was preparing an inquiry into Fairshare's operations. It took 4 months for the investigation to conclude. [65] No action resulted but our prospective buyer had moved onto other things. We ceased operations; all of us went our separate ways.

This may seem quite odd, but even though it failed, I view Fairshare as the most interesting and fulfilling business endeavor I have been involved in. It was more than a business failure…it was a Magnificent Failure!

Fast forward a decade.

- The Great Recession triggers a cascade of anxiety about how to spur economic growth.

- Young companies are recognized as job-creating engines.

- Entrepreneurialism is considered "cool", so is innovation.

- Fallout from the slow recovery is expressed as concern and resentment about rising income inequality.

- Online communities have become powerful social networks.

- A lot of money has been raised via crowdfunding.

- Policy sensibilities about capital formation are changing, as witnessed by the JOBS Act.

All these factors lead me to reprise and contemporize the Fairshare Model. A lot of people were intrigued by it. It presents a solution to the valuation challenge; something that will be more apparent as equity crowdfunding grows.

Fairshare may have been too early but today, the Fairshare Model is relevant to economic matters that are on the minds of many.

How the Fairshare Model will emerge

I believe that variations of the Fairshare Model has the potential to be widely adopted, at least for early stage public offerings. How long will it take?

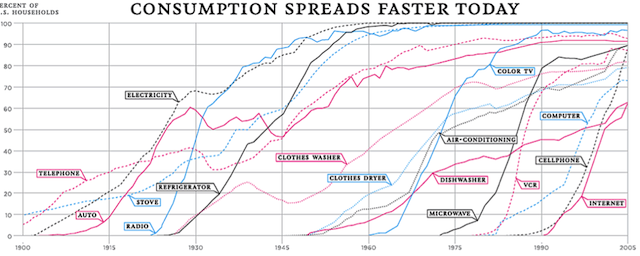

The chart below shows household penetration between 1900 and 2005 for innovative technologies that start with the telephone and electrification then traverse across a crop of appliances--refrigerators, laundry machines, TV, microwave, etc.-to cell phones and Internet. [66]

It took 25 years for 60% of households to have a clothes dryer. Personal computers took 20 years to reach 60% penetration. The Internet and cell phones took 15 years. Clearly, the time it takes for compelling new devices to be broadly adopted in the mass market is shortening.

It takes time for technical innovations to be accepted, longer for traditions to change. How companies structure their ownership interests is, perhaps, one part technical and two parts tradition.

The Fairshare Model can help companies raise capital, but that's insufficient to spur adoption. For that to happen, investors and employees need to make money—the more the better. Issuers that use the model must outperform competitors who don't.

On paper, a conventional capital structure has technical vulnerabilities that the model is positioned to exploit, but that's not enough to create change. Tradition must also weaken, which means the Fairshare Model needs multiple successes. That will take years.

The Concept Gap

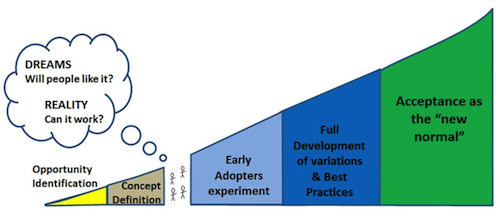

How might the Fairshare Model become more than an idea? The following chart shows the progression that I anticipate. Below it, each phase is described. The time scale is subject to Hofstadter's Law

- Opportunity Identification & Concept Definition

a. First Try

i. In the 1980's, John Wilson, begins to think about how to better match up average investors and entrepreneurial companies. Genesis of Fairshare Model.

ii. In 1994, John and I meet at a Silicon Valley environmental start-up that struggles to find the capital it needs. We determine that his idea isn't feasible.

b. Second Try

i. In 1995, the SEC announces that it will cease regulating the offer of securities and focus instead on the sale of securities, and, that electronic documents are the equivalent of printed ones. State regulators follow.

ii. John and I form Fairshare, Inc. With the help of a small team in San Antonio and Denver, [67] we develop our message and membership program. We underestimate the challenge of fitting in the regulatory framework. The dotcom and telecom bust dims investor interest in venture capital investing. We go bust.

c. Third Try

i. In the wake of the Great Recession, policy makers improve entrepreneurial access to capital. Angel investors are more active and organized. I conclude that Fairshare was too early but we were on the right track. Still, I'm mindful of the risks of being an innovator in this space.

- The Concept Gap

a. If fundamental flaws are identified with the ideas presented in this book, I have the satisfaction of knowing that I had an opportunity to air my perspective and provoke lively discussion.

b. If the concept has appeal and any flaws are fixable, the Fairshare Model will usher in a new form of capitalism, one that redefines the relationship between labor and capital by balancing and aligning their interests.

c. The test: a critical mass of interest must emerge (i.e., tens of thousands of people). Such buzz will move companies and financial experts to evaluate it.

- Early Adopters experiment

a. Early adopter companies raise capital with the Fairshare Model and explore ways to manage Performance Stock.

- Full Development of Variations and Best Practices

a. Early Adopter companies are studied to gain insight on opportunities, pitfalls, best practices and areas to explore.

b. Tradition erodes. Venture capital firms advise portfolio firms that need capital and to raise it using the Fairshare Model if they are not home run candidates. Broker-dealers will find ways to make money with it.

- Acceptance as the New Normal

a. Having established that the Fairshare Model can help companies attract and manage human capital, companies begin to consider the possibility that a conventional capital structure will be potential competitive weakness. A new era in how capitalism is practiced emerges.

Onward

This chapter concludes Section I, which describes the Fairshare Model, the problem with a conventional capital structure, crowdfunding and the history of the model. These have a micro-economic focus.

Section II will zoom out to discuss philosophy as well as two macro economic matters-growth and income inequality.

Section III will return to micro-economic issues for the Fairshare Model such as fraud and valuation.

[63] SEC staff who I presented the matter to felt similarly-a membership was not a security under federal law.

[64] In Joseph Heller's novel, Catch-22, U.S. bomber crews flying over WW II Italy are told they must fly additional missions before they may rotate to safe duty. Increasing cognizant of the risks of being exposed to the ferocious German defenses, Capt. John Yossarian asks the doctor to excuse him because he has become crazy with fear. The rule is that anyone who is crazy is not allowed to fly missions. The doctor explains that he can't excuse Yossarian from flying because of the catch-22 provision which states it is a mark of sanity to be afraid. By claiming to be crazy with fear, Yossarian proves he is sane, for only someone crazy would willing go into such danger.

[65] Our attorney, a former SEC attorney, advised that such investigations usually took at least six months.

[66] Chart from 2/10/88 New York Times Op-Ed piece, "You Are What You Spend" http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/10/opinion/10cox.html

[67] Key work provided by Walter Hodge, Jr., David Alexander, Mary Lou Hodges and Bob Lanari.

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.