The FairShare Model: Chapter Ten

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-04-10

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Chapter 10: The Tao of the Fairshare Model

Preview

- Preview

- Foreword

- A Different Approach to Uncertainty

- Uncertainty Illustrated

- The Treatment for Uncertainty-Multiple Classes of Stock

- Negative vs. Positive Energy

- Onward

Foreword

Taoism (or Daoism) is an ancient Chinese philosophy about indefinable truths underlying the universe, which are revealed in the natural order of things. Tao (or Dao) has multiple meanings but, broadly, it is a path, an appropriate way to behave and to lead others.

Ultimately, one's tao is about balance; sensing what is missing and restoring it. Everyone has their own tao and finding it requires meditative and moral exploration.

This chapter describes the tao of the Fairshare Mode—its approach to living in harmony with the uncertainty that inherent when bringing equity capital into a venture stage company. The Fairshare Model's tao—its sense of the natural order of things—is at odds with the tao of a conventional capital structure, at least the kind that are presented to public investors. That's because such a deal structure offers public investors far less protection from uncertainty than it offers venture capitalists.

On the other hand, the tao of the Fairshare Model is similar to the tao of conventional capital structure used by venture capitalists. Each seeks to balance uncertainty of performance with uncertainty of ownership. Each does it differently but that's because their audiences are different—the VC model is for accredited investors, while the Fairshare Model is for public investors.

This chapter contrasts how the uncertainty is resolved. It will also show how the Fairshare Model relies on positive energy to align the interests of investors and employees. And, it will discuss the most astonishing aspect of the Fairshare Model—that entrepreneurs become indifferent about their IPO valuation. In fact, they have incentive to make it low. Thus, it has the potential to transform the relationships between an issuer, its investors and employees in a positive way.

A Different Approach to Uncertainty

A reminder as we begin, the Fairshare Model is for a public offering, one that anyone can invest in. It's goal is to emulate the deal structure that VCs rely on when they invest in a private offering.

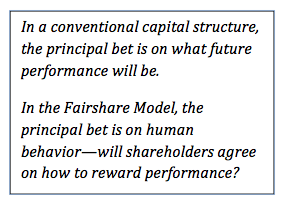

The Fairshare Model differs from a conventional capital structure in how it deals with uncertainty. Uncertainty is inescapable when balancing ownership interests and performance risk. And it can be a struggle for a company and investors to find agreement on who bears the risks of uncertainty. Any agreement reflects an answer this question…Is it better to define the ownership interests of insiders before or after performance is delivered? Or, put another way…Who should bear the risk of uncertainty, should it be insiders (employees and existing investors) or should it be new investors?

Those who believe that ownership interests should be set before performance is delivered, that the uncertainty of future performance should be borne by new investors, will favor a conventional capital structure. They presume a Next Guy who is eager to assume the uncertainty at a higher valuation.

Those who see benefit from defining ownership interests after performance is delivered or feel that the risk of uncertainty should be borne by insiders (employees and pre-IPO investors) will be intrigued by the Fairshare Model.

The essential difference between the two is when the ownership split is decided-before or after performance is established. Let's consider the distinction with a simple example and visual devices.

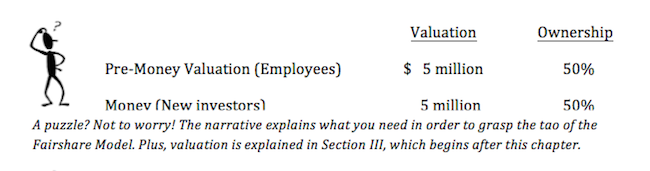

Assume that a company raises $5 million from investors in exchange for half the company. Using a conventional capital structure, the new investors and employees (a/k/a founders) agree that the issuer's pre-money valuation is $5 million (i.e., before the investor money is received). As shown below, after the new investor's money is raised, the post-money valuation is $10 million.

So, the parties have established certainty with respect to ownership—they agree the new investors get half of the equity. In doing so, the parties effectively agree that the present value [135] of the company's future performance is $5 million, even though it is little more than an idea (i.e. no performance so far). This is an important point to keep in mind.

The post-money valuation of $10 million is the sum of the value of future performance ($5 million) and the $5 million investment.

No one knows what the performance will be or what the valuation will be in the next round, when the company needs more money. The bet, the uncertainty, hinges on whether the company will meet expectations and what market conditions will be.

It doesn't matter how the parties came to value future performance at $5 million. They may have relied on a generally accepted multiple of something (projected revenue, earnings, etc.). Social considerations may have played an influence. All that matters is that the deal assumes that the company is worth $5 million before the new investors invest.

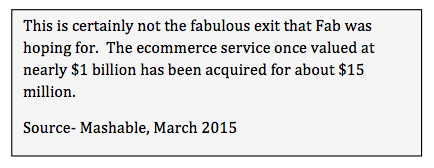

So, we have certainty regarding ownership and uncertainty about what the performance will be worth. The investors will suffer if the company is worth less than $10 million in the next round. If that happens, they overpaid. Why? Their $5 million was worth that before they bought the company's stock. Therefore, if the next round valuation is less than $10 million, the basis for the $5 million pre-money valuation in the first round was overpriced!

For example, if the next round values the company at $8 million—$2 million less than the $10 million—the first round investors should have gotten more than 50% of the ownership or they should have only paid $4 million for half.

Less apparent, first round investors may feel that they overpaid even if the next valuation is above $10 million. If their target rate of return is 15% and the next round valuation delivers 5% appreciation, they will be unhappy.

To be sure, uncertainty affects the founders too, but in a different way. They may have wistful regret if their idea/performance turns out to be worth much more in the second round. For instance, if the second round valuation is $20 million dollars, they may ask…Weren't we worth more than $5 million in the first round? Did we sell too cheap?

Chances are, though, that the founders will not beat themselves up too much about the first round valuation because it is water under the bridge. Besides, there are ways to rationalize it. They may not have gotten where they did without that money or there may have been the best option at the time.

Besides, if the next round investors must feel that they can meet their target return at a valuation that is lot higher than $10 million, everyone is happy!

|

|

Uncertainty Illustrated

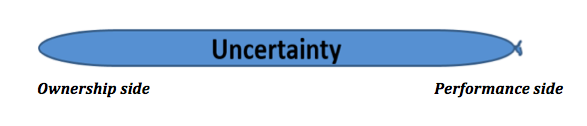

To grasp the tao of the Fairshare Model, imagine a long balloon, the kind that looks like a hot dog and can be twisted into animals and other sundry shapes. But instead of air, this balloon is full of uncertainty.

The left end of this balloon represents ownership interests in a venture-stage company, while right end represents certainty about its future performance.

And what is a venture-stage company? Regardless of whether it is privately held or publically traded, it is one that has the following risk factors for investors:

- Market for its products/services is new/uncertain

- Unproven business model

- Uncertain timeline to profitable operations

- Negative cash flow from operations; it requires new money from investors to sustain itself.

- Little or no sustainable competitive advantage

- Execution risk; team may not build value for investors

Montage

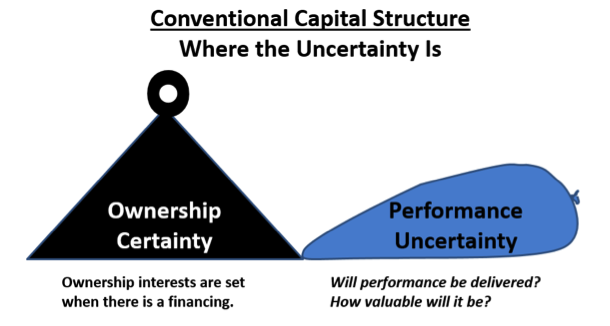

Pressing down on the balloon creates certainty, but it does not eliminate uncertainty. Certainty in one area does not reduce the volume of uncertainty, it simply moves it. A weight symbolizes certainty in our imagery. Placing the weight one end of the balloon creates certainty there but causes uncertainty to bulge on the other end.

This is a way to show that when a venture-stage company raises equity capital, uncertainty can be moved but it can't be eliminated. This is true whether the funds come from accredited investors in a private offering or from public investors in an IPO.

The balloons on the next page will help you visualize the essential difference between a conventional capital structure and the Fairshare Model. It is all about when the ownership split for investors and employees is decided—before or after performance is established.

The following balloon portrays what happens in conventional capital structure. Ownership interests are set at the time of an equity financing-the ownership spilt between employees and investors is set. It is symbolized by the certainty on the ownership end of the balloon. The creation of certainty there pushes the uncertainty to the performance end of the balloon.

Will it deliver its new product as expected? What will the market response be to the product? The answers to these question, surely, would influence the ownership outcome if they were known when it was being negotiated. But, in a conventional deal, the kind offered to public investors, ownership must be decided before the answers are known.

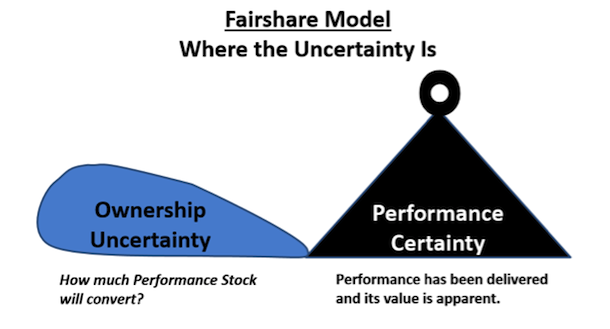

What happens in the Fairshare Model, as the next balloon shows, performance has been delivered and its value is more or less apparent. That is why the weight of certainty is on the performance end of the balloon. Placing it there moves the uncertainty to the ownership end.

Here, the uncertainty centers on how much Performance Stock will convert. Will the criteria to convert Performance Stock match the performance delivered? If there is a disagreement between the Investor Stock and Performance Stock shareholders, how will it be resolved? If either or both classes of stockholders feel the criteria for conversion needs to change, will they be able to agree on new criteria?

In the Fairshare Model, employees don't get Investor Stock for future performance, but, they do get it for past performance.

Also, future performance can be presumed, as discussed in chapter five, but the conversions happen quarterly, not up-front.

The Treatment for Uncertainty-Multiple Classes of Stock

There is no panacea for the uncertainty inherent in a venture-stage company investment, but there is a way to treat it. It involves the use of multiple classes of stock to structure control and economic interests. Venture capital and private equity firms require companies that they invest in to have a capital structure (albeit a conventional one) with multi-classes capital of stock. [136]

It is unusual, however, for an issuer to have multiple classes of stock in a public offering. When it occurs, it is to create extra voting or dividend rights for particular pre-IPO shareholders. The Fairshare Model is novel because it uses a multi-class capital structure to protect the interests of public investors.

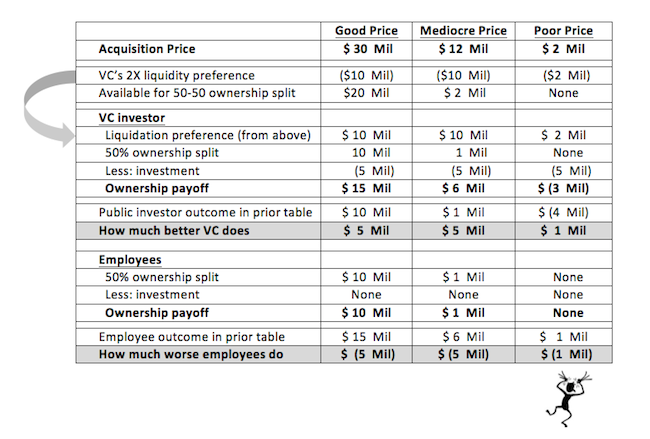

Return to our example; a new company raises $5 million at a pre-money valuation of $5 million, which makes its post-money valuation $10 million; employees and investors each own half of the company. Now, we will examine how the ownership split (here, an easy 50-50) affects the ownership payoff when the company is acquired a year later. We will first look at the ownership payoff for a company with a single class of stock, then for a company with two classes of stock.

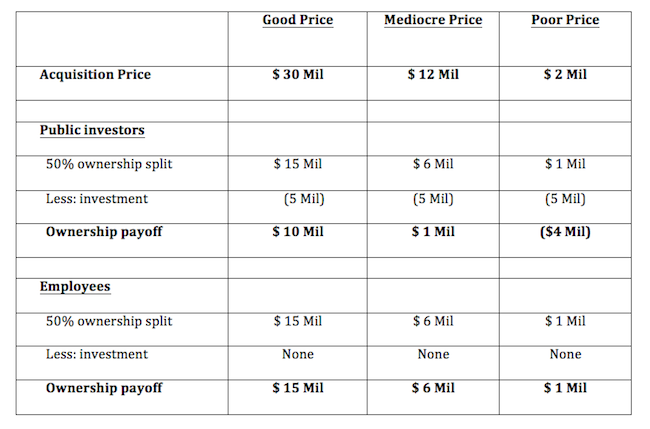

For the single stock scenario, assume that the $5 million is raised in an IPO. Again, virtually all companies go public with a single class of stock, plus, this sets up a contrast to the Fairshare Model. Also assume that no one has sold stock since the IPO, as this facilitates measurement the ownership payoffs when the acquisition price is good ($30 million), mediocre ($12 million) and poor ($2 million).

As the above table shows, in each scenario, employees do better than investors. This makes sense in the good price scenario, after all, their performance generated $20 million in enterprise appreciation ($30 million acquisition price less $10 million post-money valuation).

However, in the mediocre price scenario, the enterprise appreciation was only $2 million, which suggests the IPO valuation was too high. Nonetheless, employees get half the proceeds from the $12 sale because they have half the ownership interest (which cost them nothing). This leads to an egregious outcome—the ownership payoff for employees is $6 million and $1 million for investors, who had to pay $5 million for their 50% ownership stake.

In the poor price scenario—there is an $8 million loss in enterprise value ($10 million post-money valuation less $2 million price), yet employees get $1 million and investors lose $4 million.

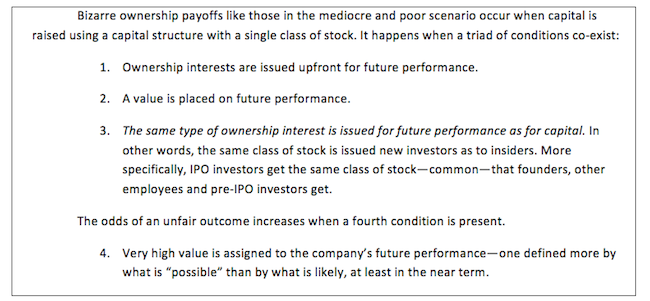

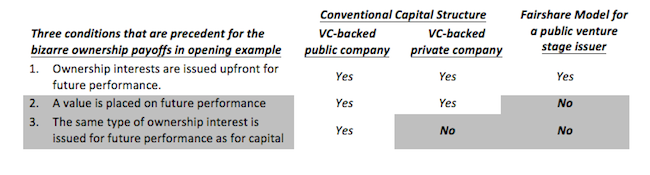

The first three conditions are the ones to focus on because they create the signature. The fourth one amplifies the risk for investors; I'll ignore it here to zero in on the essential point. The first three conditions are present in a public VC-backed company. But, the third condition does not exist in a private VC-backed company; there, different ownership interests are issued for capital and future performance.

Put another way, the capital structure used in a public VC-backed company is unacceptable to a VC when it is private. Same company, same risks—everything the same except for whether the company is public or private. If it is public, conditions one, two and three are okay. If it is private, condition one and two are okay—condition three is unthinkable!

To appreciate the significance of this dichotomy, recognize that a capital structure determines how the risks and rewards are allocated. If a corporation were a car, its capital structure would be its chassis; if the enterprise was a house, it would be the load-bearing structure; it were a country, it would be its constitution.

How ownership payoffs are distributed is a function of the capital structure. So, why do VCs refuse to invest in a private company that has condition three?

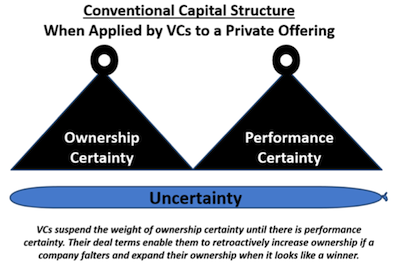

Because, as illustrated to the right, the way they deal with the uncertainty of future performance is to create uncertainty about ownership!

VCs have an array of tools to create uncertainty with respect to ownership interests. For employees, they require vesting schedules for stock issued for ideas and future performance. Shares already owned by employees may be subject to buyback or forfeiture agreements. [137] For angel investors—individuals who invest before the VC—a VC's deal terms can create uncertainty of ownership through devices that may reduce their ownership interest and/or the ownership payout. My purpose here isn't to argue whether VCs treat employees and angel investors fairly or not. It's to point out that VCs use complex capital structures to deal with uncertainty.

Accordingly, let's consider what a conventional capital structure looks like in a privately held VC-backed company. To begin with, it has multiple classes of stock. Common stock is issued to employees and other classes are issued for capital. Even when common stock is the largest class of stock, the VC's stock may be the most powerful from a control perspective (i.e., it may have the right to elect a majority of the board of directors or have super voting rights). From an economic perspective, a VC will have a priority claim to the issuer's value. Thus, ownership interests in a private, VC-backed company have an apparitional quality—it may look one way from a percentage of shares perspective and be very different from a control and economic perspective.

Now, assume that the $5 million in our example is raised from a VC. Like before, employees own half the shares. The table below has the same acquisition price range as before. It also assumes that the VC has special rights-liquidity preference, dividends, expense reimbursement and management fees—that give it priority to the first $10 million of the price. What is left is split evenly between the VC and employees.

The VC's liquidation preference provides priority to the first $10 million. "Liquidation preferences, often seen as an opportunity to juice up the returns, are rights to receive a return prior to common shareholders" [138] when there is a liquidation event, which is what an acquisition is. Here, a 2X liquidation preference gives the VC the right to twice its $5 million investment before other shareholders share the ownership payout. Multiples of one or two are common but sometimes are as high as ten. [139] Another popular way for a VC to boost its ownership payout is to secure a dividend—effectively, interest on their investment that is paid in when there is an IPO or liquidation event.

The point is, a multi-class capital structure is important to a VC. These professional investors demand insurance on the valuation they negotiate, and it is only available when condition three does not exist. A multi-class structure allows them to deal with uncertainty by creating uncertainty for the ownership interests of other shareholders. A multi-class structure also enables deal terms that increase their ownership payout above what's suggested by their ownership interest.

That is what the prior table reflects—the VC's share of the payout is greater than its 50% ownership interest. It also shows that a conventional capital structure deliver significantly different results for investors depending on whether the company has a single-class (public) or a multi-class (private) version of a conventional capital structure.

In the Fairshare Model, employees get Performance Stock for the value of their idea and future performance. In our example, the company raises $5 million based solely on an idea. Realistically, a lot of work goes into developing an idea to where investors will invest $5 million, especially if it is raised in a public offering. So, to make comparison with a conventional capital structure, assume that pre-IPO accomplishments of the employees is worth $200,000. They get Investor Stock for that. Thus, the pre-money IPO valuation is $200,000 and, after the $5 million IPO, there is $5.2 million in Investor Stock available for trading (i.e., assume no change in the price of Investor Stock). Thus, only those who buy Investor Stock or earn it via performance have shares to sell in the secondary market.

By contrast, if the IPO uses a conventional offering with a single class of stock, employees have tradable stock as a result of raising their venture capital in a public offering. This is wealth. It is generated by virtue of getting investors to fund the development of the idea. There may be restrictions on selling the stock, but they expire in a relatively short time. Creating wealth by selling a dream is nearly as old as money itself. But the Fairshare Model is different, wealth creation is tied more to delivering on the promise than selling it.

For their future performance, employees get Performance Stock—a lot! The voting power of Performance Stock is capped at 50%, however, in this example, collectively, employees have 54% of the vote but not control. Performance Stock has 50% of the total vote, plus, employees have 4% of the Investor Stock, a percentage that grows as conversions occur. Ownership payouts when there is good, mediocre or poor acquisition price are in chapter five, Target Companies for the Fairshare Model.

This section gives you a lot to think about, Dear Reader. Let's wrap up it up by reviewing what it has been about. First, it asserts that a multi-class capital structure can resolve uncertainty in a venture stage company. Then it shows how a single class stock structure, the kind used in a public company, can deliver bizarre ownership payoffs when the outcome is mediocre or poor. Three conditions that permit such payoffs are identified. Then, we see why VCs avoid one of them; why they require companies to issue different classes of stock for performance and capital. Finally, it is points out that the Fairshare Model does the same thing.

This table summarizes the three conditions and which capital structures have them.

All three models have the first condition—all issue ownership interests for future performance.

The second condition? Both the public and private company versions of a conventional capital structure require that a value be placed on that performance, but the Fairshare Model does not.

The third condition, the subject of the section, is interesting. Public companies issue the same ownership interest for performance and capital, a single class of stock. That means the financial cost of poor performance is fully borne by those who provide capital; those who have ownership interest for ideas lose an upside, time, effort and a blow to the ego, but they don't lose capital. However, when they invest in a private company, VCs require a multi-class capital structure, as does the Fairshare Model. This condition is interesting in that it isn't generally used to protect public investors in venture-stage companies, but it's de rigueur for VCs.

The tao of the Fairshare Model is to reflect how life truly is. For a person, meaning and purpose are revealed over time. For a company, value is revealed by performance.

By changing when the ownership split between investors and employees is decided, the Fairshare Model encourages public investors to support risky ventures. That's because it replicates the investor protections VCs insist on for themselves. It is merely a novel application of a proven idea.

A fairer deal for investors and entrepreneurs fosters a more equity funding for venture stage companies. This, in turn, enables entrepreneurs to pursue the Aristotelian Good Life. Vicariously, it enables public investors to do the same thing. As such, the model makes them partners, both in substance and spirit.

Negative vs. Positive Energy

Many who have negotiated a round of private capital will attest that the terms of an investment reflect the power of the parties, and, that investors want a low valuation and entrepreneurs want a high one. Getting to agreement often involves a contest of wills. The agreed-upon valuation may have terms that make the deal less attractive if the founders truly understood them. On the other side, an entrepreneurial team may oversell or deceive investors. The negotiation would be one thing if there was a "right answer" on valuation, a truth that can be revealed by argument. But, it is quite another thing because neither side knows what it is now or what it will turn out to be.

Ultimately, if a deal is done, interests are aligned, at least for a while; they fall out of alignment if things don't progress as imagined. The battle over valuation can be renewed and devolve to a struggle for control. The entrepreneurs may lose the ownership that they fought hard to get.

So, in a conventional model investors and the company begin on opposite sides of a negotiating table and may return there if things don't go well. The process has negative energy.

In the Fairshare Model, pre-money valuation isn't a battle—the process has positive energy. [140] There's no struggle between a company and its investors—because they don't begin on opposite sides of the table with respect to valuation. Investors want the valuation to be low, of course. But-this is the amazing part—entrepreneurs don't mind if it's low. In fact, they may want the IPO price low too! Ridiculously low, in the mind of companies that use a conventional model. Alarmingly low, in the mind of competitors.

If a company adopts the Fairshare Model, its directors, executives and other employees don't care what their pre-money IPO valuation is. They are indifferent as to whether it is fifty thousand, five hundred thousand, five million, fifty million or five hundred million…because it doesn't affect their financial position or voting power. What matters to them is "what does it take for Performance Stock to convert?"

If a rise in valuation—measured by the aggregate market value of the Investor Stock—is a component of performance, a low IPO valuation is in the interest of both and those new investors of Investor Stock and those who hold Performance Stock. New investors like it—after all, a low buy-in is the first half of "buy low, sell high." Employees like a low IPO valuation of Investor Stock because it makes it easier to meet the market value performance measure! For example, if a 20% rise in Investor Stock value triggers a substantial conversion of Performance Stock, employees will favor an IPO valuation that makes that a no-brainer. They also like it because it makes it more likely that any stock option they have on Investor Stock will be "in the money"—the exercise price for the option is less than the market price of the Investor Stock.

What about those who invest before a Fairshare Model IPO? How might pre-IPO investors think about a low IPO valuation? Not at all supportive, one might think. After all, if they want to "buy low, sell high" as well. It follows that "buy low, sell a bit higher" will have little appeal.

Here are some reasons why a company's angel investors might be pleased to see a company offer a low valuation with the Fairshare Model.

1. Their company gets the capital it needs….and they don't need to provide it!

- Angel investors dread having a company that will need more money than they can provide; one that struggles to find investors for the next round.

2. They avoid the threat of an ownership squeeze by that VCs may inflict when there is a down round of financing or other performance targets are not met.

- A VC's anti-dilution provisions essentially provide it with price protection. If a later transaction lowers the company's valuation, the VC gets more shares for free, reducing it's price per share and increasing its ownership share.

- A "pay-to-play" right allows a VC to investors to invest their ownership share in a new round or lose ownership position and rights.

3. Angel investors tend to have a long-term view on companies that they support. So, the low valuation in a Fairshare Model IPO may not be off-putting, given the first two points.

4. The secondary market price may be substantially higher than the offering price. The Fairshare Model IPO can reflect market value as a Black Friday sale reflects the value of a consumer product. [141] The dynamics of a low-price and small allotments may cause the share price to climb in the secondary market, even if it is a "penny stock." [142]

- Angel investors may use this opportunity to sell some of their shares.

5. Pre-IPO investors can require Performance Stock as a sweetener for supporting the deal.

6. If pre-IPO investors have warrants on the Investor Stock, they profit from the delta between the warrant exercise price, which will be at the IPO offering price or less, and whatever it rises to in secondary trading. A warrant is essentially a stock option; both are the right to buy stock at the value of the grant date in the future.

7. A Fairshare Model IPO can expand the issuer's micro-network of investors and generate favorable word-of-mouth with customers and others who can help the company succeed. If the price of Investor Stock rises in secondary trading, they will be happy.

8. Employees strive to deliver the performance that triggers conversions. This enhances the ability of the company to attract and retain employees.

So, the most likely objectors to a low IPO valuation—the issuer's pre-IPO investors—have reason to support one, if it is based on the Fairshare Model.

But how about after the raise, when things do begin to go not-so-well? A company is as sure to encounter rough seas as a ship is. Will the positive energy created by being public dissipate? Does the capital structure make a difference in how well a company weathers difficulties? If so, what might be better, a conventional capital structure or the Fairshare Model?

It's speculative to say at this point, as is the ability of companies to raise money using the Fairshare Model. That said, when things don't go well for a company, the Fairshare Model relies on positive energy to solve the problem. Reliably, management will feel pressure to take corrective action from investors but they will be pressured by employees too. After all, their ability to convert Performance Stock depends on working through the trouble—to turn lemons into lemonade.

Troubles may lead to a reexamination of the conversion criteria. This may be difficult, but achievable targets will result. Positive energy can identify pathway to success.

Can the Fairshare Model create the types of incentives that I describe in the last chapter? Could it foster the culture that helped Toyota wildly succeed? Might it be as effective as the management system that turnaround expert Q.T. Wiles used? If so, companies that adopt the Fairshare Model may outperform those that that rely on a conventional capital structure, no matter how well financed they are. For example, a company could tie Performance Stock conversion to a new product release, the acquisition of key customers, customer satisfaction measures, cost reductions, etc. And, to the extent that employees hold the Investor Stock they earn, their interests are further aligned with investors.

The potential to create powerful, dynamic alignment between public investors and employees is the most exciting aspect of the Fairshare Model. It is far, far more significant than the ability to help companies attract low-cost equity capital. This too, is the tao of the Fairshare Model.

Importantly, Performance Stock conversion could also result from raising more capital on favorable terms. It could come from a secondary public offering or a private offering.

Contrast these bad weather dynamics with those for a conventional capital structure. A VC may well have control over corporate governance matters as a result of how it negotiated its ownership stake. When it doesn't, it may have effective control via other means. Employee stock options? They don't vote. Employees are less likely to affect how problems and opportunities are evaluated and addressed. As a result, management may procrastinate or engage in top-down decisions, either of which can spawn dysfunction or reflect delusional thinking.

Negative energy is likely to seep into the environment because of the importance of the valuation in the last round. If events suggest that it was too high, wagons circle, blame is cast and factions form. By contrast, the energy in the Fairshare Model is focused on what will generate conversions—because it is forward-looking, it is more likely to channel positive energy. That's because valuation plays a far different role. A company with a conventional capital structure focuses on what needs to happen as well, but a lot of negative energy is bound to be released when some shareholders feel they were oversold, or feel that other shareholders are using the bad weather to extract advantage.

Essentially, the Fairshare Model recasts conventional ideas about corporate governance, giving employees a voice in governance. Is this a good idea? [143] Does it promote better capitalism? A more effective culture? Can a "strong-leader" operate effectively if employees have a say in corporate governance? Questions like these will be asked as interest in the Fairshare Model builds.

My sense is that giving employees a vote in corporate governance could be a positive influence for companies in any phase of development, start-up or mature, high growth or distress. Investors will gain a perspective on the company that is not controlled by the CEO. It can be of value to a CEO because employees are often a source or wisdom, and, getting their support can result in better solutions and more complete buy-in.

There will be much discussion about how voting rights should be distributed in the Fairshare Model. There will also be variation in how companies implement it. For example, some companies may have two classes of Performance Stock, one that votes and one that doesn't. In politics, comparable questions arose as feudal forms of rule were challenged. In England, the Magna Carta created the notion of a constitutional monarch—royalty required the consent of the governed (the lords, not the ordinary people). The formation of the United States of America radically transformed the relationship between those who govern and those who are governed. The French revolution had similar aspirations—Liberty, Equality, Fraternity—but their experiment descended into a morass that presaged, in some ways, the authoritarian mess that became known as communism more than a century later. Nations have conducted numerous "who can vote" experiments over time—companies that adopt the Fairshare Model will do the same.

Onward

This chapter concludes Section II, which began by examining a range of ideas about two macro-economic concerns that provide context for the Fairshare Model—economic growth and income inequality. It then considered how the ability to cooperate creates might offer diverse ways to address these twin challenges and how Fairshare Model promotes this. This chapter identified two structural elements that determine how a capital structure allocates uncertainty in an equity financing, something that will inform the discussion about economic growth, income inequality and equity crowdfunding. It also presented the most remarkable aspect of the Fairshare Model—it provides venture-stage companies a reason to offer public investors a low valuation. As a consequence, the model enables a well-performing team to create more wealth for themselves than if they use a conventional model and to create competitive advantage when it comes to managing human capital.

The tao of the Fairshare Model is clear—it is to balance the interests of entrepreneurial companies and public investors.

This section has been broad in content and philosophical perspective. Section III returns to narrower micro-economic matters, issues that come into play when venture-stage companies raise venture capital in a public offering—valuation, fraud and failure.

[135] "Present value" is the value today of a future stream of income or cash, discounted for risk and time. A dollar that you get in five years is worth less than a dollar today-that's the present value.

[136] Private Equity (or PE) is a superset of venture capital: all VC firms are a form of PE. VCs focus on private, early-stage companies while PE firms invest in established businesses, both private and public.

[137] There are vesting schedules for stock options too.

[138] "The Business of Venture Capital", Mahendra Ramsinghani, John Wiley & Sons (2011), page 239

[139] Ibid

[140] This dichotomy evokes a famous comedy routine performed by the late George Carlin that contrasts baseball and American football. You are sure to laugh even if you have little interest in sports. To view it, do a web search for "Carlin baseball football" or use this link http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aIkqNiBASfI

The text is here http://www.baseball-almanac.com/humor7.shtml

[141] Wikipedia: Black Friday is the Friday following Thanksgiving Day in the U.S. and regarded as the beginning of the Christmas shopping season. Many retailers open very early and offer sales to kick off the shopping season. Violence may occur between shoppers competing for access to the limited supply of deeply discounted items.

[142] Wikipedia: Penny stocks are shares of public companies that trade at low prices per share. In the U.S., a penny stock is one that trades below $5 per share, is not listed on a national exchange, and fails to meet other criteria.

[143] In Europe, many companies give employees the right to appoint a member of the board of directors.

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact: Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.