The Fairshare Model: Chapter Four

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-04-10

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Chapter 4: Crowdfunding and the Fairshare Model

Preview

- Foreword

- Crowdfunding is not a new idea

- Risky Deal Access vs. Risky Deal Quality

- The Drama -- in Opera!

- Self-Responsibility

- Registered vs. Unregistered Offerings

- Equity crowdfunding is not a totally new idea either

- Prospects for crowdfunding via Wall Street

- The Intermediary Problem for DPOs

- A role for intermediaries who are not broker-dealers?

- Perspective on intermediaries who are not broker-dealers

- Regulation of equity crowdfunding platforms

- Onward

Foreword

This chapter expands on my statement that the Fairshare Model is not equity crowdfunding as you know it. A key point will be the difference between an innovation in distribution and an innovation in structure.

It also provides some high-level perspective on the policy issues facing equity crowdfunding as envisioned by the JOBS Act.

It is an examination of tectonic fault lines, not a "how to"crowdfunding guide. The SEC final rules for the JOBS Act have not been released for comment—they are expected in 2015.

Crowdfunding is not a new idea

"Crowdfunding"seems new, but it isn't. It's been practiced for a long time in three forms: rewards, donation and credit. [21] Let's touch on examples of each before discussing equity crowdfunding.

In the early 1700's, Benjamin Franklin (yes, that one), wanted to start his own printing business but he didn't have the money to buy printing presses. The enterprising young man used rewards-based crowdfunding; he raised the money by offering the reward of future printing services at a discount. Rewards-based crowdfunding is used to raise money to develop a new product or service from supporters. In rewards-based crowdfunding, contributors receive no financial stake in the company's success, because they don't get stock. And, it's not money that is repaid if the product or service isn't produced or doesn't meet expectations. The incentive for someone to "invest"is part transactional (i.e., secure a deal) and part what fuels donation-based crowdfunding; the motivation mix will vary.

Donation—based crowdfunding is collecting money to support a cause or project. Clearly, it's been done for ages by groups of like-minded people. Intriguingly, the Statute of Liberty was the result of a donation-based crowdfunding campaign in France and the United States.

Credit—based crowdfunding is also an old practice, particularly in communities that have little or no access to affordable commercial lending. A popular variety is a group of people who contribute money to build a modest pool of capital that is available to help those with poor access to credit. The loans are often interest free—but borrowers are expected to repay the loan.

In the 1800's, Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver's Travels, reportedly had such a fund for those suffering from the Irish potato famine. In the 1970's, Dr. Muhammad Yunus developed concepts for micro-credit lending and founded Grameen Bank to implement it in Bangladesh. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his pioneering work.

Non-institutional credit-based crowdfunding has been in place for generations where institutions are weak or expensive. Kiva.org has made more than a million micro-loans totaling more than half a billion dollars with a repayment rate of 99%.

Why would someone give money to such an effort? To fund a source of support for people who need it, of course, but there's more to it. It combines the altruism of donation-based crowdfunding with the satisfaction that one is getting something for it, a self-renewing resource that encourages the type of industrious activity that reduces the need for charity.

Distribution vs. Structure

The Fairshare Model is not crowdfunding as you may understand it. Equity crowdfunding is an innovation in how shares are distributed (i.e., how new stock in a company is sold). On the other hand, the Fairshare Model is an innovation in how they are structured. What does that mean?

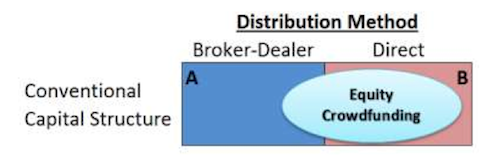

The chart below illustrates that there are two methods that a company can use to distribute its stock, hire a broker-dealer or sell it directly to investors. Equity crowdfunding is an innovation in distribution because it promises to make it easier for companies to sell stock.

There are two things to note. First, equity crowdfunding is a new way to sell a deal based on a conventional capital structure. That is, an offering in which a value must be placed on the issuer's future performance. Thus, it is likely to increase the exposure public investors have to overvalued companies—because setting the value involves a high degree of speculation. Second, equity crowdfunding can be used by broker-dealers. The box marked "A"indicates that the bulk of shares in underwritten IPOs will be distributed in the traditional manner but a portion might be crowdfunded. Box B similarly projects that most, but not all, DPOs will rely on crowdfunding.

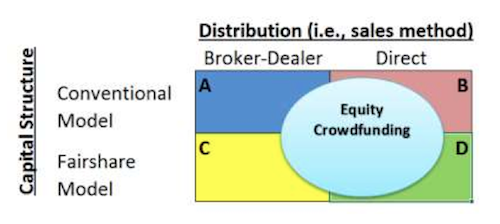

The next chart adds the Fairshare Model and illustrates how is both distinct from and complementary with equity crowdfunding. It is an alternative structure for a public offering, regardless of how it is sold. Crowdfunding will make it easier to sell an offering and reduce the cost of capital, regardless of whether the shares are sold by a broker-dealer (boxes A and C) or directly by the issuer (boxes B and D).

Companies that adopt the Fairshare Model can sell shares via broker-dealers (box C) or directly (box D). Either way, they are likely to utilize equity crowdfunding.

Risky Deal Access vs. Risky Deal Quality

Virtually all debate about equity crowdfunding has centered on the wisdom of expanding access that young companies have to investors and vice versa. Let's add a new dimension—how to improve the quality of a risky deal that is sold to public investors. As you may recall from chapter two, that objective appears in the tail end of my vision for the Fairshare Model. Here it is again.

Middle Class investors will be able to make venture capital investments on terms comparable to those that professional investors get.

Crowdfunding enthusiasts embrace the first portion, that Middle Class investors will be able to make venture capital investments; they want it to be easier for companies to sell their stock to average investors. Of course, since the stock is based on a conventional capital structure, there is the valuation challenge. [22] There has been little discussion about how to deal with it.

On the other side of the debate, crowdfunding opponents fear that investors will lose money. They certainly will! Companies that use crowdfunding will be risky and have a high failure rate. But, rather than take the approach of early 20 th century prohibitionists—outlaw alcoholic beverages—I suggest a different, less paternalistic tack.

Recognize that there are many legal ways for people to be foolish with money (i.e., lottery tickets, frivolous expenditures, casinos, etc.). Also, that there are plenty of smart, savvy, unaccredited investors who want to invest in young companies.

So, why not explore ways to make the risky activity less harmful? Advocate moderation and diversification to investors that want to invest in startups. Support investor education about deal terms. Urge the SEC to require that all issuers disclose and discuss their valuation in their prospectus (more on this in the valuation section). These actions may reduce the likelihood that investors will lose more than they can afford when buying stock in a conventional deal. And, of course, promote discussion about the Fairshare Model! Because an understanding of capital structures leads to more savvy decision-making.

Anyone interested in improving financial markets may have something to say about the second portion of my vision statement. The Fairshare Model is one way to accomplish it.

What other ideas are out there? Can a conventional deal be made "safer"for average investors? What other models should be considered?

The Drama -- in Opera!

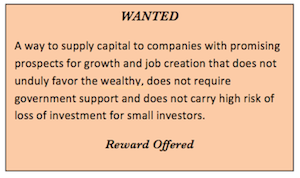

So, as the preceding suggests, a drama is unfolding. Think of it as an opera. The opening is sung by a baritone voiced character who laments the poor state of the economy, the inadequate supply of jobs and rising income inequality. He declares that his search for a solution has led him to conclude that improving access to capital for entrepreneurial companies should help. His aria cites economic reports. For decades, he sings out, more jobs have been created by emerging growth companies than by Fortune 500 companies. [23]

All the other characters on stage nod and express enthusiasm for the idea. They sing as one glorious and coherent group. It's stirring.

Then, one calls out, "Where will the money come from?"

Cacophony ensues.

One calls out for tax incentives for the wealthy, but he is shouted down by others who sing out "no more, no more."Another cries out for government to use tax proceeds for the capital, but she too is shouted down by a different group who also sings out "no more, no more."Still another makes the case to allow small investors to step in but here, again, the clamor is loud, this time, the song is "not safe, too risky."Fading in and out between each of these group's cry is a chorus who laments for better, simpler days.

The question—"Where will the money come from?"—remains. If it is controversial for government or small investors to provide the capital, that means it is up to wealthy investors to do it. But that contributes to income inequality! After all, as one player points out, the return on venture capital investments has been attractive enough to attract a growing amount of capital.

Our opera ends with the characters agreeing on what they want. They write it on a poster.

As the lights slowly fade, the poster (box to the right) is raised for the audience to see.

They then sit down and wait, huddled in their respective groups, eyeing one another with suspicion.

Self-Responsibility

That tongue-in-cheek opera simplifies the drama surrounding equity crowdfunding because this book is about the Fairshare Model, not the JOBS Act. The model does not need the JOBS Act, but, interest in it will surely rise with crowdfunding because the valuation problem of a conventional model-the need to set one for future performance—will become conspicuous to more people. [24]

Securities attorney William Carleton, frequently blogs about the JOBS Act. He feels that equity crowdfunding for unaccredited investors cannot be effectively implemented without a "re-do"to fix contradictions within the law that were created as the JOBS Act bill moved through the legislative process. Two solutions that he proposed to Representative Patrick McHenry of North Carolina, the originator of the bill, are in the scope of our discussion. They appear below. [25]

Investor protection

Create a bright line: "you are not allowed to lose more than this amount annually."

Propose that in any 12 month period, no investor is allowed to invest more than $1,000 in a single issuer, or more than $5,000 in equity crowdfunding deals in the aggregate. No need for a prospectus, audited financial statements, lawsuits against entrepreneurs, or other actions that are a burden or a threat to entrepreneurs.

Should anyone call for additional investor protections, knock a zero off the two investment limits. Make the single offering limit $100, and the annual aggregate limit $500. And then say, "if the experiment works at this modest level, we can consider increasing the levels in a few years."

There simply has to be an amount which reasonable people can agree are so modest that protections – which are a boon to lawyers but a tax on utility – are not worth their cost.

Entrepreneur protection

Put the onus of annual investment limit compliance on the investors. No need for entrepreneurs (or funding portals) to collect investor W-2s to verify income, then stress on how to meet privacy regulations.

Instead, require the investor to self-police. If she invests in excess of the limits, she is forever barred from bringing claims under the Securities Act against the entrepreneurs to whom she made false reps.

If regulators insist that investors may be confused by the responsibility, then require this mandatory disclosure:

Prospective investors please note: you are likely to lose everything that you invest in this offering. Don't invest anything that you can't honestly regard as play money.

And it's even worse than that in the following respect: if we (the issuer) do something wrong, you can only go after us legally if you have kept your equity crowdfunding investment under the annual limits imposed by law.

It's not our job to police whether you have exceeded your annual limits. It's your job, and you exceed them at your peril.

So, recall our opera. Some actors scoffed "not safe, too risky"at the idea of non-accredited investors to providing capital to entrepreneurs. Carleton speaks to their concern by combining a limit on investor exposure with an incentive for the investor to observe it. This a sensible approach to explore. Those who want to invest may do so. The risk is communicated starkly. Significantly, an investor loses legal remedies if s/he violates the limit, and, little legal or financial burden is placed on the parties (i.e., investor, issuer, broker-dealer or portal).

Securities law and regulation generally places the burden of determining investor suitability on the issuer and/or broker-dealer. The JOBS Act continues this tradition and makes portals similarly responsible. In the case of a private offering they are now expected to verify that an investor who claims to be accredited meets the criteria. Prior to the JOBS Act, issuers with a private offering could generally rely on an investor's representation. In the case of private offerings exempt from registration (discussed next), issuers are required to enforce the limits that Carleton describes. This reflects a world view that companies should be responsible for investor behavior and, of course, there is a long history of people being duped in securities, that's why they are regulated. But, there is also a long, deep history of people being duped to make unwise expenditures that are not regulated . My elderly mother, for example, spent an imprudent amount on overpriced gold coins after seeing television pitches about how they were a good investment. If TV networks were liable for disseminating misleading information, she would not have been induced to make such an unwise "investment."But, it doesn't work that way.

For public offerings exempt from registration (also explained next), the JOBS Act limits the amount an investor may invest in a given offering AND annually in similar offerings. It is difficult for anyone but the investor to monitor. Plus, any system to do this raises privacy and data security concerns. It is a dream for litigators and a nightmare for anyone interested in a reasoned approach to opening up capital markets. How to parse the responsibility between the issuer and investor is a key question. Policy makers must balance the risks associated with innovation and opportunity against the desire to protect average investors in a cost-efficient manner.

Carleton's solution has a King Solomon-like line ---There simply has to be an (investment) amount which reasonable people can agree is so modest that protections are not worth their cost.

I say, let's find that amount and start to experiment!

Registered vs. Unregistered Offerings

Before completing our detour, let's distinguish a registered from an unregistered offering. [26] Opponents of equity crowdfunding don't want it to be easier for companies to sell stock in an unregistered offering but few oppose initiatives to make it easier for companies to sell a registered offering.

Some equity crowdfunding opponents may think that registration reduces business risk, but I don't see how. Registration increases disclosure. It doesn't mean that an offering earned a regulatory Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval; that doesn't happen. Nor, for example, does it reduce the risk that revenue will meet expectations. Some believe that registration disclosures ward off investors from an unwise investment. It does, provided an investor (or someone they pay attention to) reads and grasps the disclosures. The point is that a company with high business risk can register its offering. Now, under certain conditions, registration can reduce liquidity risk for existing shareholders because it enables them to sell their shares to other investors.

So, what is registration? Generally, to sell stock to U.S. investors, a company must register the offering with securities agencies with jurisdiction for those investors. The process requires an issuer to provide a registration statement that describes its business, the securities to be sold, has information about its management and audited financial statements. A portion of the registration statement is also known as the prospectus, offering document or selling document—it is what is typically provided to investors. It also may include material that is not in a prospectus, like major contracts.

Each state has a securities agency and there is, of course, the federal agency, the SEC. State securities laws are commonly known as Blue Sky Laws in the sense that they seek to protect investors from investments that resemble an opportunity to own a piece of the blue sky above, which is a poetic way to describe a fraudulent or highly speculative business proposition. There is little uniformity among blue sky laws even though about forty states utilize a shared model. So, each state has its own set of securities laws and its own review process. Same goes for other forms of law.

If a company plans to sell securities to investors in multiple states, it can simplify this process by registering its offering with the SEC. Under certain circumstances, the SEC has full authority over the registration statement; there is no state review.

Now, add a twist. Federal and state securities laws exempt (or excuse) certain types of offerings from their full registration requirements. When an exemption is relied upon, complications can arise. The chief one is that states need not accept the SEC review as the sole determinant of a lawful offering. That said, the principal federal exemption must be accepted by states. That's an offering that qualifies under Regulation D (a/k/a "Reg D") of the Securities Act of 1933 (a/k/a the Securities Act). [27] A Reg D offering may only be sold to a limited number of accredited investors. When angel investors, venture capital or private equity firms invest in a company, it's likely to be via a Reg D offering.

Okay, we're about to enter a zone of controversy. Some exempt offerings can be sold to unaccredited investors. This effectively makes the issuer public because investors have tradable stock.

Why is this allowed? It is an effort by government to reduce the cost of raising capital for small issuers by simplifying or scaling down disclosures, a "mini-registration statement", if you will. For instance, an issuer may not be required to have audited financial statements. This experiment has taken various forms over recent decades but it hasn't been used to great effect. Why?

- First, there is an easier path for companies that only target accredited investors-- Reg D offerings have few restrictions and disclosure requirements, relative to an exempt offering that may be sold to unaccredited investors.

- Second, regardless of whether the offering is registered or exempt, a DPO issuer has the "intermediary problem", which we'll discuss in a few pages.

- Third, while federal securities law can trump state laws when an offering is registered, when a federal exemption is relied upon for an offering that can be sold to unaccredited investors, state law is not preempted. As a result, the process of clearing an exempt offering in multiple jurisdictions can be time consuming because states require adherence to their own law and their own review. An offering under Regulation A (a/k/a "Reg A") of the Securities Act is exempt from registration and it can be sold to unaccredited investors. It is a mini-registration both in substance and format. Title IV of the JOBS Act authorizes an increase in the allowed size from $5 million to $50 million (a so-called Reg A + offering), but it will not be effective until the SEC releases its rules on Title IV of the JOBS Act. In conjunction with the to-be-finalized Title III rules for equity crowdfunding, the Reg A+ offering will figure prominently in the modernization of capital formation.

Think back to that opera. Add a platform at the back of stage, so that some performers stand above the others and position the federal actors above state actors. All the earlier voices are there, but now the regulators are singing their aria in a discordant manner.

Granted, I take artistic license here. But consider how securities attorney Samuel Guzik describes the conflict between the federal and state regulators over the anticipated increase in the maximum size of a Reg A offering to from $5 million to $50 million.

Both the scope and breadth of the SEC's proposed rules appear to represent an opening salvo by the SEC in what is certain to be a fierce, long overdue battle between the Commission and state regulators, the SEC determined to reduce the burden of state regulation on capital formation-a burden falling disproportionately on small business-and state regulators seeking to preserve their autonomy to review securities offerings at the state level. [28]

Equity crowdfunding is not a totally new idea either

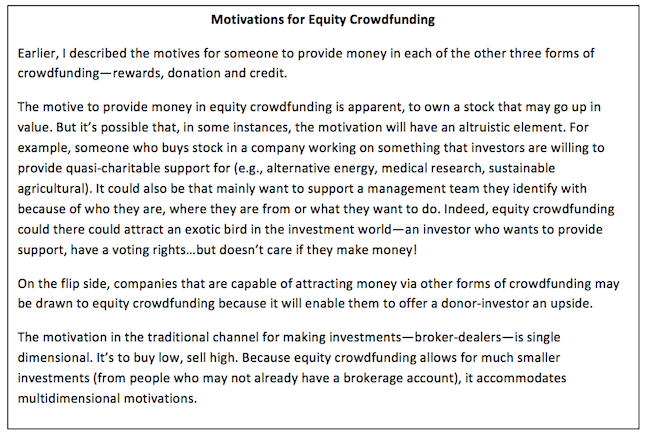

Okay, detour done, what about "equity crowdfunding?"Surely, that's a new idea. It's what people get excited about when they contemplate new ways for companies sell stock online using websites such as Kickstarter, Indigogo, RocketHub, etc.

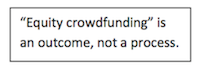

However, in my view, equity crowdfunding is not a new idea; it has been available for decades. It occurs when an issuer makes its stock available to average investors in modest amounts. Put another way, equity crowdfunding is an outcome, not a process. So, any new form of equity crowdfunding allowed under the JOBS Act is additional way to achieve an outcome that has been possible for years.

So what ways were available to make new shares of publically tradable stock available to average investors in modest amounts before the new law? A direct public offering (DPO) or an offering sold by a broker-dealer. Title III of the JOBS Act authorizes a third way—the use of online investor portals to facilitate the offer and sale of securities—that will make a DPO easier to sell. The law allows such platforms to be run by parties that are not broker-dealers, so long as they have oversight from FINRA or a new SRO. This is difficult for some regulators to support because traditionally, they have just had to police broker-dealers. Hence, equity crowdfunding as anticipated by the JOBS Act remains a chimera; there is no third way…yet.

Virtually all DPOs are crowdfunded. They tend to be undertaken by young companies whose offering size is relatively small (i.e. $7 million or less). A pre-Internet DPO pioneer was Real Goods Trading Corporation of Ukiah, California, a solar equipment retailer. In 1991, Real Goods raised $4.6 million in two direct public offerings by soliciting its mail order customers, winding up with 5,000 investors. The Internet era pioneer was Spring Street Brewing Company, a New York microbrewer. It's CEO, Andrew Klein, a former securities attorney, posted offering documents on the brewery's website and advertised it on six-packs. It raised $1.6 million from about 3,500 investors. [29]

The second way to achieve equity crowdfunding is via an underwritten offering. But, as an idealistic entrepreneur discovered, Wall Street banks are not keen on giving average investors access to shares. In 1995, Boston Beer Company, maker of Samuel Adams beer, raised $75 million in an underwritten IPO. Founder James Koch said they had to overcome strong resistance from its investment banks and had to go through difficult regulatory hoops to make it possible for its customers to buy a few shares at the offering price (about an $500 investment). Here's what Koch told the New York Times.

You really have to fight the whole system: the investment bankers, the S.E.C., the current regulations,'' said Mr. Koch, noting that Goldman, Sachs, one of his underwriters, refused to handle the consumer deal. ''The entire regulatory system is not set up to allow shares to be available for consumers.'' [30]

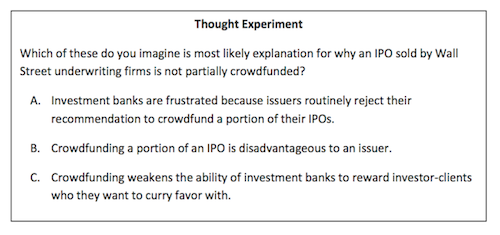

Prospects for crowdfunding via Wall Street

Have things changed in the 20 years ago since Boston Beer did a Wall Street version of "Fight the Power"? [31] Is it easier to crowdfund a significant portion of an underwritten IPO?

Koch said that the SEC and securities regulations were an obstacle to his crowdfunding effort. I can imagine why, but significant changes to securities regulations have taken place over the past two decades. The mindset of a number of regulators has been evolving. More change may well be called for, but, the most significant barrier to equity crowdfunding right now may come from the securities industry, not from government.

The SEC states that "it does not regulate the business decision of how IPO shares are allocated."A post on its website titled "Initial Public Offerings: Why Individuals Have Difficulty Getting Shares"makes the following points. [Note: the SEC's language is italicized; I add bold for emphasis.]

- Underwriters and the company that issues the shares control the IPO process

- Most underwriters target institutional or wealthy investors in IPO distributions.

- Brokerage firms must consider if the IPO is appropriate for individual investors in light of their income and net worth, investment objectives, other securities holdings, risk tolerance, and other factors. A firm may not sell IPO shares to an individual investor unless it has determined the investment is suitable for that particular investor. [32]

- Even if the firm decides that an IPO is an appropriate investment for an individual investor, the brokerage firm may sell the IPO only to selected clients. For example, before you can purchase an IPO, some firms require that you have a minimum cash balance in your account, are an active trader with the firm, or subscribe to one of their more expensive or "premium"services . In addition, some firms impose restrictions on investors who "flip"or sell their IPO shares soon after the first day of trading to make a quick profit.

So, if government doesn't hinder equity crowdfunding in Wall Street IPOs, what does? FINRA [33] , the securities industry's self-regulating organization (SRO), may discourage broker-dealer (a/k/a underwriters) members from facilitating equity crowdfunding in a variety of ways. FINRA, not the SEC, sets investor suitability and other requirements to protect investors. These rules are also intended to reduce legal exposure from disgruntled investors.

A cynic might wonder if FINRA rules that hinder crowdfunding might also reflect a desire to protect the interests of the industry's most powerful players. After all, many of its decision-makers come out of the broker-dealer community itself. And, there is a duality to the nature of a SRO. On the one hand, it exists to keep government from directly regulating its industry. On the other hand, it acts like a trade guild, protecting the interests of its members. As discussed in "The Problem with a Conventional Capital Structure"chapter, the business models of investment banks rest on positioning their investor-clients to profit from buying the new shares of their issuer-clients. In other words, keeping hoi polloi [34] in back of the line to buy shares in a IPO appears to be the raison d'être (i.e., "reason for existence"in French) for Wall Street firms. [35]

But, let's suspend cynicism for a moment. Presume that FINRA, like the SEC, is neutral on how Wall Street firms distribute IPO shares. Boston Beer was conspicuous in its effort to crowdfund a significant portion of its IPO and other issuers have encountered similar resistance. So, what is going on here? Why don't we have more crowdfunding via Wall Street IPOs? Is it hard to do? Or, is it not in the interest of the underwriters?

Hmmm…investment banks have lots of resources; they routinely hire some of the brightest people and pay them humongous amounts of money. So, I'm guessing that the obstacle to crowdfunding isn't that it's just too hard to do. I'm going to go with the second choice-equity crowdfunding doesn't usually happen in a Wall Street IPO because its not in the interest of underwriters and they discourage issuers from pursuing it.

The Intermediary Problem for DPOs

So, what are the prospects for equity crowdfunding? If it was economically beneficial for underwriters to do so, Wall Street banks would routinely crowdfund. If any of them felt it was the right thing to do, some might support issuers that want to do it. If there was requirement to do so, they would, but there isn't one, and, unaccredited investors are not organized to make that happen. [36]

So, if Wall Street investment banks are to support crowdfunding, it will be because issuers like Boston Beer Co. press them to. And if that is what we have to wait on, my forecast for crowdfunding via broker-dealers is "cloudy with a chance of disappointment."That's from the perspective of investors. The outlook is gloomier for small companies because they lack the clout of an issuer like Boston Beer.

What about DPOs? Issuers who sell shares directly to the public love crowdfunding. But, they can benefit from an intermediary, as can investors. When an intermediary can provide value, not having one is problem. There is an overarching problem, however; the opportunity for intermediaries who are not broker-dealers is often closed, narrow or uncertain.

The intermediary problem comes into focus as one compares the challenges faced by a DPO issuer to those faced by homeowners who tries to sell their house without a real estate broker-dealer. In both cases, the seller is unlikely to have a list of prospective buyers. Nonetheless, the seller must make potential buyers aware of their deal (i.e., a DPO or a home). In real estate, this is easier if buyers are looking in the neighborhood because, at any point, there will be just a few homes available. With a DPO, however, there's a sea of competition for a buyer's attention.

In real estate, buyers are reluctant to view a property for sale by owner. In securities, buyers may be reluctant to download and read a prospectus. In both cases, buyers may be reluctant to engage the seller directly in due diligence. In real estate, buyers often are under pressure buy (i.e., need a place to live or mortgage rates are going up). There is no comparable "need"to buy a stock.

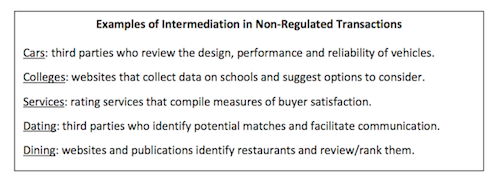

The box shows a range of interactions where it is uncontroversial to use an intermediary. It is human nature to want one, even if we will decide what to do ourselves. They can make introductions, minimize awkwardness, plus, provide information and perspective on how to evaluate something.

A role for intermediaries who are not broker-dealers?

Should parties who are not broker-dealers be allowed to facilitate a securities offering ? [37] Put differently, should average investors be able to screen companies and share due diligence using websites that are not run by broker-dealers? [38] Or, put yet another way, for average investors, must the sole solution to the intermediary problem be broker-dealers?

This question is a large part of what the equity crowdfunding debate is all about. It asks whether society is best served by allowing new intermediaries help issuers sell their securities. If Wall Street IPOs were allocated in a democratic manner, the question would not interest so many people. If innovative companies were satisfied with the cost of raising capital, the question would not be as significant as it is.

If the answer to this question remains "no", the prospect for equity crowdfunding dims. That's because there is little reason to believe that Wall Street banks will alter their behavior. Also, because the intermediary problem that hinders the use of a DPO will persist.

Perspective on intermediaries who are not broker-dealers

For decades, accredited investors have joined together to educate themselves about investing, to screen deals and pool due diligence on them. The Band of Angels, possibly the first organized angel investor group, was formed by a dozen individuals in San Francisco in 1994. The popularity of this form of interaction grew. In 2000, the Keiretsu Forum was formed in the San Francisco Bay area to build on this concept. [39] Today, it is the world's largest angel investor network with more than 1,400 accredited investor members in 34 chapters. The growth in the number of such groups led to the formation of the Angel Capital Association in 2004; it has more than 160 angel groups and more than 7,000 investors.

Angel groups facilitate investments (i.e., make them easier). Before the JOBS Act, doing so risked violating securities regulations because they were not regulated. As a result, meetings routinely began with a benediction like this; "Nothing we discuss here is to be construed to be an offering of securities, which can only be made by a broker-dealer."Then, they went on to facilitate investments.

The need for this fan dance weakened in 2013, when the SEC announced JOBS Act rules that allow non-broker-dealers to facilitate investments by accredited investors online. Now, so-called angel investor portals may list private offerings, provide matchmaking services and facilitate due diligence. But, a portal may not charge success-based compensation. In order to do that, some affiliate with or become a broker-dealer.

For unaccredited investors, "investment clubs"provide similar benefits involving securities in the secondary market. The National Association of Investors Corporation—also known as www.BetterInvesting.org —has a membership of 50,000 individuals, most of who are in an investment club. Formed in 1951, the organization reached a peak membership of 400,000 in 1999. Investment clubs are like book clubs, but they discuss investing concepts and stocks. The Internet has reduced the appeal of formal investment clubs because there are many websites that provide education about investing and facilitate due diligence of stocks.

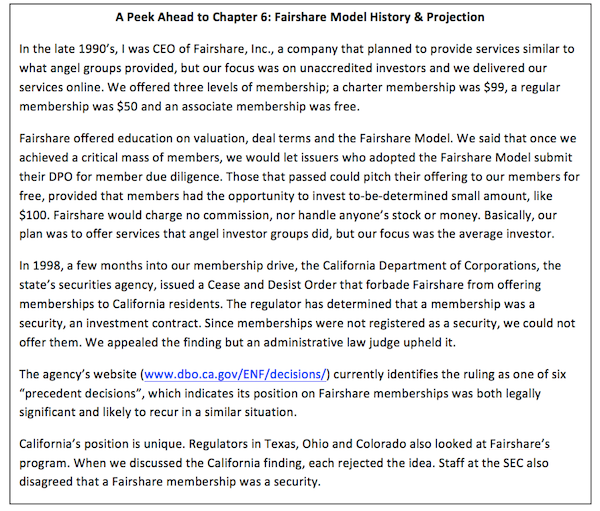

As the following anecdote illustrates, facilitation of direct public offerings is controversial. That's because it involves unaccredited investors, and, it does not fit cleanly in the regulatory framework.

So, five regulatory agencies (four states plus SEC) see the same evidence. One finds that a Fairshare membership is a security and four don't. The 1994 movie Forrest Gump has a line that captures this situation—Life's like a box of chocolates, you never know what you're going to get .

Life is a learning experience and here is what I learned. [40]

- It is easy to create an investment contract in California. For a free Fairshare membership, all that was required was a name, address and email address. Our paid memberships promised nothing other than our best effort to do things that we said we might not be able to do (i.e., attract DPOs that met our criteria). Nowadays, the membership fee might be considered a form of reward-based or contribution-based crowdfunding…but probably by the California securities agency, given the evelated status it gave its ruling on Fairshare memberships.

- Texas, Colorado and Ohio wanted to see Fairshare a regulated entity, not necessarily a broker-dealer. Our immediate services-investor education and community interaction—were not a problem. But, the services that we aspired to provide at an indeterminate future point—deal screening, shared due diligence and allocations of shares in DPOs—tested the boundaries of regulated and unregulated activity. When we created a subsidiary that was registered with the SEC as an investment adviser, their concern went away.

Regulation of equity crowdfunding platforms

Title III of the JOBS Act calls for a crowdfunding portal to belong to FINRA or another national securities association. In other words, the law requires them to operate under the umbrella of a regulatory authority. This is consistent with what Texas, Colorado and Ohio state regulators told me about Fairshare in the 1990s. In a backhanded way, its what California said when it found Fairshare memberships to be securities; it has the effect of requiring Fairshare to be a broker dealer or hiring a broker dealer to offer a membership.

So, the consensus among policy makers is that there is a possible role for non broker-dealers in facilitating DPOs. Now the question is, should the regulatory authority be FINRA or something else?

FINRA is a not-for-profit organization, not a government agency. Its website points out that it has 3,400 employees in 20 offices who oversee more than 4,100 securities firms with 640,000 brokers, so its large and well established. It is funded by the financial industry itself, not by tax dollars. Its member-firms pay membership fees, plus, FINRA also collects fines from members who violate its rules; it's website reports that it levied $75 million in fines and restitution from fraudulent traders in 2013. [41] The argument for requiring crowdfunding portals to be FINRA members rest on these robust capabilities.

The arguments against FINRA as the regulatory authority crowdfunding portals include:

- FINRA has conflicts of interest as it is heavily influenced by Wall Street banks. It is therefore unlikely to manage oversight of crowdfunding portals in a way that allows them to threaten the interests of its powerful members.

- FINRA may smother crowdfunding portals with compliance demands designed for broker-dealers. They are different; the brokerage business is profitable and crowdfunding platforms may struggle to establish financial viability. Also, the average crowdfunding transaction size will be vastly smaller it is for FINRA members.

- FINRA regulators may handicap innovative crowdfunding business models because they don't "get"it (i.e., it's too different from what they normally see). [42]

- In industry, concentration of power often hinders competition, stifles innovation and leads to higher prices. Concentration of power in regulatory rulemaking and enforcement could have a comparable effect.

Two national associations have been formed in the U.S. for equity crowdfunding platforms; the Crowdfund Intermediary Regulatory Advocates (CFIRA) and Crowdfunding Professional Association (CfPA). They are small and lack financial viability but this could change when the SEC issues rules for crowdfunding platforms. That will allow companies to define business models and for these organizations to define membership fees that fit most models.

Another possible solution is for the SEC to provide direct oversight of crowdfunding portals. The agency already does this for Investment Advisers, who also have a national association, the Investment Adviser Association. The SEC's website describes them as "a variety of financial professionals provide services to help individuals manage their investments."For compensation, Investment Advisers advise others as to the value of securities and the advisability of buying or selling them. Investment advisers may include money managers, investment consultants, financial planners, general partners of hedge funds.

Whichever regulatory oversight path is selected, it is evident that the nascent industry will need more financial support than it can generate from membership fees. So, those charged with raising that support may be a bit like Blanche DuBois from Tennessee Williams's play A Streetcar Named Desire . She has the memorable line---"I have always depended on the kindness of strangers ."The strangers for a crowdfunding SRO will be in the form of sponsorship deals from FINRA, the Investment Adviser Association, companies in the financial services sector and angel investor groups.

Equity crowdfunding platforms have the potential to disrupt the financial services industry the way that Walmart altered the retail business and Charles Schwab redefined the brokerage business. It will take at least a decade for the experiment to play out.

Onward

Having discussed the Fairshare Model, conventional capital structures and crowdfunding, the next chapter will speculate on to the categories of companies may be attracted to the Fairshare Model…if enough people make it clear that they like the model.

[21] Tip of the hat to Kim Kaselionis, founder of Breakaway Funding, LLC (www.breakawayfunding.com) for pointing out the heritage of crowdfunding.

[22] See chapter three, "The Problem with a Conventional Capital Structure."

[23] In the 1984 movie Amadeus, the Austrian emperor presents Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart with a challenge. Compose an opera in German, rather than in the traditional language, Italian. Mozart questions whether German is mellifluous enough for opera, then accepts the commission. So, Dear Reader, be like Mozart; imagine that economic reports can be delivered in operatic form.

[24] The Fairshare Model could be used today in a Wall Street IPO-but early adopters are likely to be DPO issuers.

[25] "Does the U.S. Equity Crowdfunding Legislation Need a 'Do-over'?"by William Carleton, Crowdsourcing.org, http://www.crowdsourcing.org/editorial/does-the-us-equity-crowdfunding-legislation-need-a-do-over/19913

[26] I bow to Sara Hanks at CrowdCheck in appreciation for her insights. CrowdCheck (www.crowdcheck.com) provides due diligence and disclosure services for online alternative investments.

[27] One of the three Reg D exempt offerings (Rule 506) provides a federal exemption from registration that supersede state rules. The other two Reg D offerings (Rules 504 and 505) do not trump blue sky laws.

[28] "Regulation A+ Offerings-A New Era at the SEC", by Samuel S. Guzik, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation,

http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/corpgov/2014/01/15/regulation-a-offerings-a-new-era-at-the-sec/

[29] William K. Sjostrom, Jr., Going Public Through an Internet Direct Public Offering: A Sensible Alternative for Small Companies?

[30] "Boston Beer: The Sad Fall Of an I.P.O. Open to All"; by Reed Abelson, Nov. 24, 1996; New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/1996/11/24/business/boston-beer-the-sad-fall-of-an-ipo-open-to-all.html?smid=pl-share

[31] The rap song "Fight the Power"by Public Enemy was used to conspicuous effect in the opening credits of Spike Lee's 1989 film, "Do The Right Thing."It's on YouTube http://youtu.be/U35MvblI4og

[32] Ironically, a broker-dealer might deem an investor unsuitable for an IPO allocation but allow the same investor to buy the same stock in the secondary market. From a cynical perspective, an unsuitability finding reinforces the prevailing Wall Street business model-position a firm's best customers to profit by moving them to the head of the allocation line. From an investor protection perspective, it shows how difficult it is to enforce suitability standards, after all, an investor could place a buy order with a firm that doesn't have one.

[33] FINRA is the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, the SRO that resulted from the 2007 merger of the regulatory arms of the NYSE and the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD). The NASD is no more, but the NASDAQ echoes its name; it is the acronym for National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations.

[34] Hoi polloi is an English expression derived from a Greek word that refers to the common people, the many, or "the unwashed masses."The Occupy Wall Street movement gave us "the 99%", which has the same meaning (i.e., the opposite of "the 1%"or the privileged few).

[35] Per Wikipedia, before 1860, most early U.S. corporations sold shares in themselves directly to the public without the aid of intermediaries like investment banks.

[36] As discussed in "The Problem with a Conventional Capital Structure", the interests of public investors are split between those who get IPO allocations and those who are not.

[37] Facilis, the Latin root of facilitate, means to make easy.

[38] Generally, attorneys, accountants and financial advisors are allowed to facilitate introductions and due diligence but this isn't a practical approach for average investors who want to invest a modest amount.

[39] Keiretsu is a Japanese term for a group of affiliated corporations with broad power and reach. Keiretsu Forum is a conglomeration of individuals or small companies that are organized around private equity funding for mutual benefit. Keiretsu Forum believes that through a holistic approach that includes interlocking relationships with partners and key resources, they can offer an association that produces high quality investment opportunities. [Source: http://www.keiretsuforum.com/about/ ]

[40] As Fairshare began its membership drive, I sent information about it to the SEC but received no response. About two years later, as chapter six describes, I discussed the investment contract argument with SEC staff; they did not view a Fairshare membership as an investment contract.

[41] Restitution is collected by FINRA and paid out to investors who were harmed by FINRA members.

[42] Dividend Reinvestment Plans (DRIPs) are a way for shareholders to buy additional stock directly from the company, without a broker-dealer. This type of programs is nearly a century old. Thought experiment: If DRIPs were a new idea, would FINRA promote or hinder it?

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.