The Fairshare Model: Chapter Three

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-04-10

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Chapter 3: The Problem with a Conventional Capital Structure

Preview

- Foreword

- Praise for a Conventional Capital Structure

- The Fundamental Problem: Valuation

- Private Investors Get a Valuation Cushion

- Public investors bear the weight of the fundamental problem

- You may ask yourself…

- The Next Guy Theory of Pricing

- Market Forces

- Its considered "normal

- Competitive market forces are weak.

- Value Add

- A bigger neighborhood

- Public investors bear the weight of the fundamental problem — Redux

- Public investors have no price protection

- The basis for an IPO valuation is speculative

- Undemocratic allocation of IPO shares (which glues the other three risks)

- Public investors have the most to lose from an excessive valuation

- Recap

- Bird's-Eye View of Possible Outcomes: Conventional vs. Fairshare Model

- Onward

Foreword

Valuation is the Achilles's Heel of a conventional capital structure. A conventional deal structure demands a valuation, but it's difficult to arrive at a rational one. When the negotiating parties settle on one, it is fraught with uncertainty.

Private investors have ways to use a conventional capital structure to cushion themselves from the valuation conundrum. Public investors do not.

The best way to encourage reflective about the potential for innovation in capital markets is to talk about a conventional capital structure at its weakest point, which is how it affects public investors. This chapter does that for people inclined to defend The-Way-It-Is-Now. Its goal is to expose the belly of the beast, to spark discussion of the drivers of tradition in the relatively new market for public venture capital.

Praise for a Conventional Capital Structure

Before preparing to bury Caesar, let me first praise him. A conventional capital structure has numerous, substantial advantages:

- Proven over decades of use and applied in a range of situations;

- Simple to understand;

- Private investment funds are comfortable with the structure;

- Of course, they know how to modify it (i.e., make it more complex) to protect their interests in a private offering;

- It works better for professionally managed investment fund managers (i.e., VCs and PE funds) than for individual angel investors;

- It works, in the IPO market, but better for companies, for investment banks and investors they seek to curry favor with than for average investors;

- It's understood by service providers (i.e., legal, tax, accounting and valuation firms) who work for companies or investors;

- It's understood by stock analysts

- It's understood by securities regulators; and

- The media doesn't try to explain it because it's status quo.

Not bad for complex socio-economic process.

Cartoonist Gahan Wilson sets the tone for this chapter

The Fundamental Problem: Valuation

Praise aside, a conventional capital structure has a fundamental problem, an Achilles' heel. At the time of an equity financing, it requires the issuer and investors to set a value for future performance. For venture stage companies, this is hard to do in a rational manner.

You can test this assertion even if you are a novice about capital structures and valuation. When you meet someone who raised money for a company or who has invested in one, ask "What was the valuation?"Follow that with "Why does that make sense?"

Chances are that you will see uncertainty and anxiety play across their face. Why? It could be that they don't know what the valuation is. Perhaps, they know the number but not how to calculate it. Very possibly, they don't know how to evaluate it, or, they are not confident that it makes sense.

Still, a value must be set for future performance. This is the fundamental problem of a conventional capital structure—the need to settle a question before there is evidence of what the answer should be. I refer to it as the Achilles' heel because the Fairshare Model attacks the conventional structure, which is strong and seemingly impervious to injury. The "arrow"is embodied in how the Fairshare Model settles the performance question—it waits until there is evidence.

Valuation is what the parties agree the entire company is worth. If an investor wants to make a profit, they should pay attention to valuation because he/she only makes money when someone buys their stock for more than they paid for it.

The problem is that it is hard to determine, rationally, what the value of a company should be, especially if it is early-stage. Yet, a conventional capital structure demands one. That is the source of the uncertainty and anxiety; you have asked your conversation partner about something important that they may not understand well and/or can't justify in a sensible manner.

How hard is it to come up with a rational valuation? Imagine that you are required to assess a class of elementary school children for who will be a success in life. Define "success"any way you like. You have as much information as you want about the kids, so, you have clues that about who may achieve success. You struggle because you know that life is uncertain. It takes unpredictable turns. Qualities that will be important in each child's future may be unknown to you. Or, they may be difficult to assess.

If you were actually forced to make this assessment, it would be hard. Time would reveal that you were wrong in many instances. The success of each child is difficult to predict reliably because, in reality, success does not lend itself to prediction. It reveals itself over time and with perspective.

Entrepreneurs and investors are similarly challenged when setting a valuation—but from different perspectives. Entrepreneurs think their future looks bright. Their backers clearly do too, but they don't know if the entrepreneur's confidence will be borne out. Even though the company's success will reveal itself over time, the players must set a valuation.

So, the central problem for a conventional capital structure is that it does not reflect the way life actually plays out. It requires a decision on something that is difficult to assess and that assessment is often wrong.

A derivative problem is the lack of transparency in valuation—neither the figure nor the rationalization for it is a required disclosure for issuers. Valuation is a material consideration for a savvy investor. The figure is largely arbitrary but there are many who profit by dressing it up in artificial mystery and complexity. The valuation section will further discuss this and make proposal for how policy makers can make valuation and the reason for the amount chosen transparent for average investors.

Private Investors Get a Valuation Cushion

When investing in a start-up company, institutional investors sidestep the valuation problem by demanding what are known as "anti-dilution provisions", a non-intuitive term that amounts to price protection. If later investors buy in at a higher valuation, all is well. If the valuation doesn't rise high enough, investors with price protection get additional shares for the money they initially put in. In other words, the valuation they initially bought in at is reduced retroactively: more shares for the same money means a lower price per share or valuation.

Sellers of goods and services often offer consumers price protection by offering to match another seller's price. It's an inducement to get buyers to buy from them instead of a competitor. The buyer knows they want the product/service because it is of use or value to them (economists call this "utility").

Investments are different. They don't have utility; you can't eat, wear or otherwise consume an investment. An investor invests with the expectation that what is acquired will appreciate in value. But, it's hard to know what a private company's value is unless and until there is a liquidity event (it's acquired or becomes publically traded).

To induce a professional investor to buy-in at its valuation, companies must offer price protection. Put another way, VCs rely on more on price protection terms to avoid overpaying than they rely on their ability to identify the right valuation number.

So, for accredited investors, particularly professional ones, a conventional capital structure works well; they can reduce the risk of overpaying.

Public investors bear the weight of the fundamental problem

The weight of the valuation problem falls heaviest on public investors and it has four interlinked facets.

1. Public investors have no price protection

2. The basis for an IPO valuation is speculative

3. Undemocratic allocation of IPO shares (which glues the other three risks)

4. Public investors have the most to lose from an excessive valuation

These four facets are discussed at the end of the chapter. Before that, let's consider why the valuation problem falls heaviest on public investors when a company uses a conventional capital structure.

Two concepts explain why. The first is the Next Guy Theory of Pricing.

The second is that market forces in the capital markets are not strong enough to benefit public investors. If they were stronger, issuers would compete for public investors based on valuation and terms. That they don't compete is prima facie evidence of weak market forces in the IPO capital market.

You may ask yourself…

An IPO establishes a benchmark for a company's market value….but what does that value reflect when the company is a startup? It's performance? It's risk? More buyers to compete for shares? Less savvy buyers? A bit of all that?

Going public is not a controlled experiment on value. An IPO does not compare what wealthy pre-IPO investors feel the company is worth to what wealthy public investors feel it is worth.

A new, active ingredient is in the mix when a company has a public offering—average investors who have been unable to invest earlier. Their involvement effervesces the valuation for two reasons. First, they generally are valuation unaware. Second, they are enthusiastic, as it is their first opportunity to invest in the company. The dynamics of these factors creates demand that is relatively price insensitive—what economists call "price inelasticity"—for the supply of shares. Competition for shares by eager, valuation-unaware investors bids the valuation up from whatever the issuer decided to set it at to begin with.

Is there an intrinsic value for a venture-stage company?

If not, how about a "fair"value? One established by investors with relatively similar information and opportunity to invest?

Is a company's value fairly measured in a private offering, where investors have price protection?

Is it fairly measured in the IPO or secondary market trading that immediately follows?

If each of these is a fair measure, what explains the remarkable increase in valuation that typically occurs in the quarters leading up to an IPO and then after?

You may ask yourself, is it performance or is it something else?

You may ask yourself..."How did I get here?" [19]

The Next Guy Theory of Pricing

When explaining valuations to Fairshare members in the late 1990's, I described my Next Guy Theory of asset pricing. The economic climate has shifted over the ensuing years but the idea still makes sense and it doesn't require a fancy economic equation.

The Next Guy theory is that for an investment, the price is no more than what the buyer believes the Next Guy will pay, less a discount.

| Expected Price a Future Buyer Will Pay | $ XXX |

| – Discount Required |

(YYY) |

| = Price Present Buyer Willing to Pay for an Investment | $ ZZZ |

So, if an investor believes the Next Guy will pay $10 per share and the buyer's minimal return is, say, 25%, the investor will pay no more than $7.50. I ignore the time value of money and the element of risk to focus on the principal driver—what the buyer—investor believes the Next Guy will pay.

The Next Guy Theory does not explain the price that a buyer will pay for necessities (food, medical, fuel, shelter, etc.), for pleasure (fashion, travel, entertainment), for a gift or for other non-investment purpose (vanity, status, guilt). These all have a possible combination of utility value, status value and emotional value. An investment rarely has these qualities.

The theory does explain buyer behavior when evaluating an investment. Consider real estate; the dominant determinant of price is whether the buyer believes he is getting a price that is lower than what someone will pay later. The buyer may have non-investment motivations; they need a place to live (consumption), they may love aspects of the property (pleasure) or other factors may be in play. But, if investment is the sole motivation, the price a rational buyer will pay for real estate will be a discount from what they expect the Next Guy will pay.

Ditto for cars, art, jewelry, although here, like in some investments, the concept of utility applies. You may, for example, be willing to pay more for something that reflects your social sensibilities, the image you want to project and so on.

For companies, the Next Guy theory explains why a rise in valuation isn't necessarily explained by performance. Instead, it's explained by who is doing the buying—public investors. Ergo, when measured by a conventional capital structure, valuation is a function of "who"is buying, not "what"is sold, as expressed in these concept equations.

Valuation = ƒ [ Who the investor is]

Valuation ≠ ƒ [ What the company's performance is]

Market Forces

The Next Guy valuation function explains pricing for investments, but it can also apply to products that have utility, like clothing or food, where wholesale/retail pricing models are used. Now, think about how the wholesale/retail concept applies to the venture capital market. Let's break down the components that you recognize in the trading in goods and reassemble them in a novel way. It will provide a new perspective about how market forces are neutered when it comes to capital formation.

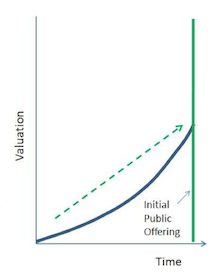

So, what is the "product"? It is equity (stock) in a venture stage company, and, it is sold to investors in both the private and the public capital markets. Here, the "manufacturer"is the issuer and it sells its product to private investors at wholesale and to public investors at retail. As the prior chart illustrates, the rise in valuation as a company approaches an IPO can be substantial. So, comparable product, different pricing.

Wait! Check that last thought for a moment! The products are not comparable, they have important differences. The product sold at wholesale to pre-IPO investors, the institutional ones at least, is much better than the retail version. As described earlier, the stock that these investors get have price protection and other features. The product sold to public investors lacks such features. So, the retail buyer gets an inferior product …and pays more for it!

Can you think of another market—a competitive market—where that happens? I can't.

Take note of that last point, then, put it to the side. It's important, but it is a distraction from the big question. That is "What accounts for the increase in valuation of the manufacturer's (issuer's) product (equity) as it approaches an IPO?"The Next Guy Theory provides insight, but what are the drivers? What might be going on? Here are four hypotheses I've come up with.

1. Its considered normal

2. Competitive market forces are weak

3. Value add

4. A bigger neighborhood

Its considered "normal"

The first hypothesis is that everyone thinks its normal for a company's value to increase when is public. The ability to buy and sell ownership shares is a good reason why it should—it makes it easier and less expensive to attract future capital. But, "Do the reasons explain the scale of the increase?"Could it be that "normal"means "it happens all the time"as opposed to "it makes sense?"After all,

Many things that once were considered normal no longer are. Sometimes, because of new ideas. Sometimes, because those who were disadvantaged under the old norm assert their influence.

Competitive market forces are weak.

The second possible reason for the valuation rise is that weak market forces characterize the market for public venture capital. If competitive forces were strong, issuers would compete for investors by offering lower valuations. In virtually every sector of a vibrant, market-based based economy, where demand exceeds supply, sellers compete for buyers. Why doesn't that happen in public venture capital?

Young companies struggle to raise capital. There is high demand for it. And, there is a significant supply of investors with interest in such companies, as witnessed by their interest in IPOs. So, why don't companies routinely compete for public capital? Why don't entrepreneurs say "We're having a sale!"or "Our terms are better!"? I think the overarching reason is that market forces are weak in the capital markets, insofar as public investors are concerned . Nobody has incentive to compete in this way. Neither issuers nor investment banks do. And, public investors with the clout to change things actually benefit from The-Way-Things-Work-Now.

Issuers lack incentive to offer lower valuations because it reduces the wealth and control of its pre-IPO investors, including management. They view a discounted valuation the way that a cat views the prospect of a bath. They…well, um, resist. But, institutional VCs have the clout to break that resistance. When the pool of potential buyers is small, as it is for private offerings, these buyers decide what they think the Next Guy will pay and what the discount will be. Issuers can accept the deal offered or keep looking. On the other hand, in a public offering, the pool of buyers is large and none have as much clout as a VC in a private offering. The most powerful use their influence to secure shares that they can flip to the Next Guy…other public investors.

Investment bankers are uninterested in promoting competition for public capital because it complicates their business model. It's not easy to say "we represent the finest companies"then, turn around and say "this issuer has a better deal". Consumer brands face a similar dilemma with discounting but many have made "premium factory outlet stores"work. They sell discounted merchandise there while selling it at full price elsewhere. Something similar should work for broker-dealers.

So, issuers and broker-dealers lack incentive to compete for public investors based on deal terms. Surely, though, some would though if they felt there were was a large potential audience for such a pitch.

You might think that public investors who want better terms have to make some noise! But the investor who is willing to play sets the terms. Fact is, many investors are valuation-unaware-they don't know what constitutes a "deal."This problem has two components. First, one needs to know what the valuation is-many don't. Second, one needs a context to evaluate it. In real estate, it is easy to get comparable sales data, not so for stock offerings. You can help change that. Chapter __ describes how to let the SEC know that you support a valuation disclosure requirement for all stock offerings.

An additional solution is to reprogram the game, to change what is considered normal. Chapter __ describes the most intriguing aspect of the Fairshare Model; it changes the calculus for issuers in a public offering. It provides them incentive to compete for investors by offering lower valuations.

As it gains acceptance, issuers with a conventional capital structure are likely to see public investors challenge their valuations. How might such companies respond? Some might adopt a variation of the advertising tag line used by a hair-coloring product-"L'Oreal. It costs more, but I'm worth it!"

Value Add

The third hypothesis is "value-add", which can explain most of the wholesale/retail price difference in many products. Wholesale buyers buy it in a more "raw"form than retail customers. To transform it to a "finished"state that retail customers expect, the product must be processed further. In this analogy, the issuer may need further development before it is presented to retail investors. Such work by the entrepreneurial team constitutes value-add. Since it is supported by and often guided by institutional VCs, some refer to this as a VC value-add.

It is easy to argue that a VC value-add exists. It's their guidance and network. Also, their ability to write large checks and attract other VC money. One challenge for companies that adopt the Fairshare Model is how to replicate the VC value add. To be clear, it is a challenge for issuers that adopt the model, not for the Fairshare Model itself. Similarly, a conventional capital structure was not first designed for VCs; it existed when the first wave of modern VCs were in college. Over time, they tweaked it. A similar phenomenon will occur with the Fairshare Model as it gains popularity.

Yes, it is easy to argue that a VC value-add exists but it is not easy to define it a manner that adequately explains the wholesale/retail valuation gap. Part of it may be due to performance, but what proportion? Part may be attributable to a celebrity effect. If Company ABC is backed by top VCs, retail investors are interested too. But they can't get allocations of IPO shares, they must buy in the secondary market. Some are like teenagers swooning over a chance to see the hottest heartthrob; their eagerness to invest surely contributes significantly to the gap.

A significant portion of the difference, I suspect, is not due to professional investor involvement. VCs differ in their abilities, plus, some do not create considerable value-add. Yet, the public virtually always pays a valuation premium. So, we're talking about a concept that's a bit nebulous.

Interestingly, I've seen investment bankers and other service providers boast that they "build value"because they help companies move from the wholesale to retail capital market. They don't make the company fundamentally better or less risky—they usher it into a different plane of valuation. It's a significant task in a number of respects, but the reward that they reap can be outsized. After all, they don't invent, design or manufacture the issuer's product, expand its market or they improve its operations. From an investor's perspective, the movement from private to public doesn't change a business any more than moving a caterpillar from one place to another makes it a butterfly—that transformation takes time.

Defenders of a conventional model may challenge this characterization, arguing that public investors only get to invest in the most promising companies-that private investors assume great risk by investing at an earlier stage and the sharp rise in valuation is their just due. While, I have respect for the value that seasoned, connected advisors can provide a company my counter argument is that the reduction in risk is a weak explanation for the scale of the rise in valuation; the increase is routinely disproportionate, hugely so.

A bigger neighborhood

What about that fourth possible reason? Does a bigger neighborhood influence valuation? I think so because investments such as real estate, art, etc. sell for more in areas with dense populations than those that are less so. Here's a conceptual equation for the idea.

More Potential Buyers = Higher Potential Demand = Higher Potential Price

A house or art in Peoria is not inherently worth more than in Chicago, but there are many more potential buyers in Chicago. And because those buyers imagine exposure to even more buyers when they are ready to sell down the road, the Next Guy Theory amplifies the present value of an investment beyond what buyers in Peoria have.

It is not stretch to imagine this phenomena playing out in securities as well. Moving from the private market to the public market is the inexact equivalent of moving a house or art from a small market to a big one. It is inexact because some public markets, like the NYSE and NASDAQ are attractive, and some, like the Pink Sheets are not. And the Pink Sheets, the backwater of the secondary markets, is where small cap stocks trade. Entering the public market may help explain a rise in valuation for venture-stage companies but it's a weak justification for it. A company that is hard to rationally value is exactly that, regardless of the market it is in.

From a fundamental perspective, the public/private valuation dichotomy presents a distinction where there is no difference. That is, the transition from private to public does not improve a company's revenue or profits. Neither does it reduce its overall risk. So, from a fundamental perspective, this conceptual equation is true.

Private Venture-Stage Company = Public Venture-Stage Company

From a market perspective, however, a risky company that is public may be worth more than a similar private company. Intriguingly, the entry into the public market is associated with more value that being in the public market. This is why a private equity fund may take a company private by buying all its public shares. After a further investment to reinvigorate its performance potential, the PE firm will have an investment banker take it public again. The change in valuation is explained both by fundamentals (better performance) and a form of arbitrage between the two markets.

Public investors bear the weight of the fundamental problem — Redux

Earlier, I asserted that the weight of the valuation problem associated with venture stage companies falls heaviest on public investors. With both the Next Guy Theory and the weak market force argument in mind, let's revisit the four possible reasons that this is so.

Public investors have no price protection

A conventional capital structure has no price protection for public investors. If they overpay, they lose. Public investors pay more for undelivered performance than private investors. They don't have the type of price protection that professional pre-IPO investors get.

There is no Next Guy who will value undelivered performance highly. As the IPO fades in the rear view mirror, new investors will increasingly rely on actual performance. Therefore, public investors in a newly public stock bear the risk of overpaying in ways that other investors do not.

The basis for an IPO valuation is speculative

A conventional model demands a valuation for a company's future performance. It works for private investors because they get price protection on later investment rounds. Intellectually, it does not work for public investors. For them, in VC jargon, a conventional model "does not scale". That's because:

1. Techniques used to value a mature businesses don't work well for a venture-stage company;

2. Venture-stage companies are notoriously difficult to value using any other technique; and

3. Price protection is not available.

Therefore, a conventional capital structure is a valuation tool for public venture capital the way a hammer is a tool for a bolt. But practically speaking, it is the only deal on the menu. Issuers who adopt the Fairshare Model will offer a deal similar to what private investors get. Can a conventional capital structure be modified to do that? Perhaps, we'll find out if there is significant interest in the Fairshare Model. Until then, it is what it is, a tool that doesn't fit the need of public investors.

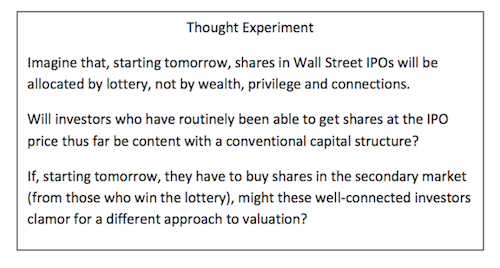

Undemocratic allocation of IPO shares (which glues the other three risks)

If IPO shares were allocated by lottery, democratically, if you will, I imagine that there would be calls from the most influential public investors (those who get allocations now) for a deal structure that was similar to those private VCs get. Various forms of protests by organized groups of buyers would apply pressure on issuers. Market forces in would cause things to change.

But, the interests of public investors are bifurcated. There are those who are favored by investment banks to get an allocation of shares at the IPO price because of their wealth, power and influence. Then, there is everyone else—and few of them are valuation-savvy. Neither group has had a voice on valuation but the first group doesn't care—they get in front of the second group when shares are allocated and then sell shares to them in the secondary market. So, the interests of public investors are in two camps, privileged IPO investors who may have an ephemeral desire to hold the stock and secondary market investors who are gleeful at the prospect of being able to invest.

In politics, high-minded rhetoric about the welfare of the population at large is routinely deployed. In reality though, politicians decide matters to appease their base of support and those with influence (i.e. campaign contributors). Is it farfetched to suspect that something similar happens in public venture capital? Might those with the influence to change the-way-it-works-now be the beneficiaries of the-way-it-works-now? Surely, defenders of the-way-it-works-now will reference the majesty of free markets. But, what if those forces are gamed in a way similar to how politics are? Would the uneven approach to valuation and other investor concerns be framed as a problem or a product of market forces?

Admittedly, this point is not a "risk"to public investors per se. But, it is a factor that glues the other three risks that I list, so, I include it.

Public investors have the most to lose from an excessive valuation

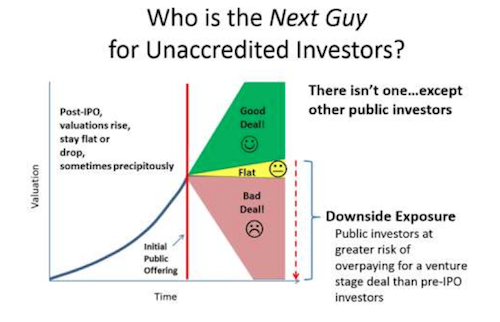

As the chart below shows, there is no Next Guy for the majority of public investors, the unaccredited ones. Thus, they collectively face the greatest risk that loss from an excessive valuation.

When performance expectations are not met, a stock is likely to drop. The loss may be absorbed by a large number of investors. An atomized loss, one spread over many investors, is not conspicuous, even to the victims of an excessive valuation. Indeed, most will view their loss as "just a bad bet". They don't realize that the fundamental premise of a conventional capital structure—that a valuation of future performance must be set when an equity transaction occurs—is flawed.

Recap

How durable is this situation? Time and time again, we see markets evolve as a result of sellers competing by offering buyers better value. Examples abound:

- Food and over the counter drugs: generic or private label vs. branded

- Books: Amazon vs. book stores

- Real Estate: web-listings vs. the Multi-Listing System limited to broker-dealers

- Clothing: designer knock-offs vs. designer labels

- Stores: Factory outlet vs. department stores, or, warehouse (Costco) vs. traditional retail

Can a similar dynamic be applied to equity investments in venture-stage companies? It's likely, I think, if the SEC requires all issuers of equity securities to disclose their valuation and how they rationalize it. [20]

For public investors in a venture-stage company, a conventional capital structure has two essential problems. The basis for a high valuation is shaky, and, they assume most of the risk that it is too high. Four linked elements comprise the foundation for this problem.

1. Pubic investors pay "retail"for venture-stage investments but don't know it.

2. They are not offered a better deal because they don't demand it.

3. They don't demand it because they are not valuation savvy.

4. They aren't valuation savvy because securities regulators don't require valuation disclosure, and, companies see no benefit from stating what the valuation is and why they set it there.

"So it goes", Kurt Vonnegutt might say.

I assert that the Fairshare Model is well suited for venture stage companies raising equity capital from public investors because it avoids the need to value future performance.

Bird's-Eye View of Possible Outcomes: Conventional vs. Fairshare Model

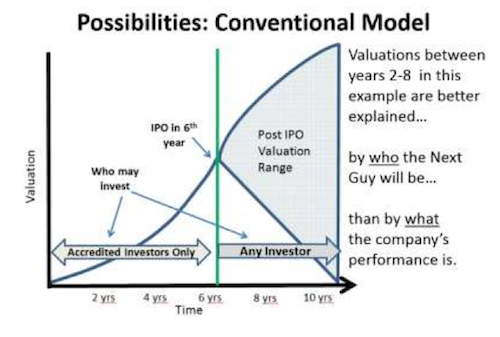

Let's return to the charts from chapter one that show how public investors could be positioned in a conventional capital structure versus the Fairshare Model. The first illustrates the range of possible outcomes for public investors with a conventional capital structure. It assumes the issuer is backed by accredited investors until it goes public in year six. Until about year eight, its valuation reflects who the Next Guy is. After, it reflects how the company is performing.

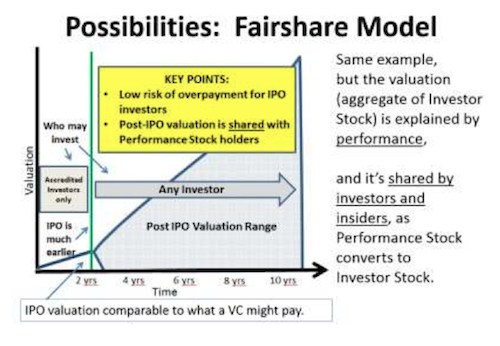

The next chart illustrates how the Fairshare Model is different. Here, the issuer goes public sooner, in year two, at a much lower valuation. If it performs, the increase in valuation is shared by the investors and employees. If it doesn't perform, public investors will lose less because the IPO valuation was lower.

Onward

This chapter argues why public investors should be interested in upending tradition in public venture capital. Now that you learned about the Fairshare Model and its nemesis, a conventional capital structure, let's explore crowdfunding. That's a hot topic nowadays.

[19] With a nod and smile to the Talking Heads and their song "Once In A Lifetime".

[20] More on this in Chapter__

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.